What do we know about politics and stock markets? In summary:

- Stocks of politically connected companies perform better. Political connections have economic value to the companies that enjoy them, and investors benefit.

- Stock markets are indifferent to the party in charge. This doesn’t mean that policies don’t matter, just that knowing who is in charge doesn’t tell us much by itself.

- Investors don’t like international crises – stock returns are lower, and volatility is greater when crises are active.

- In times of political uncertainty, stock markets become more volatile, but average returns are not predictably affected.

Read on if you’d like to know more about the election and how or whether it may affect your portfolio.

These are turbulent times in our country’s political life. Commentators largely agree that there is polarization in the views of the major political parties and their supporters. Our legislators seem to argue much but accomplish little. Political expression on social media seems to grow ever more strident.

Political uncertainty is uncomfortable in many ways. Investors might reasonably want to know whether and how this uncertainty and discomfort might translate into investment returns.

As you might imagine, there has been considerable professional interest in this question. You may remember that I wrote an article just before President Trump’s election about the likely impact of his presidency on the stock market, and that I cited an academic analysis. It turns out that the paper I cited was just the tip of the iceberg. There are at least one hundred published papers on politics and the stock market. Fortunately, I can draw on a “literature survey” article which summarizes the published work.

Wisniewski (the survey author) divides potential impacts into categories:

- Whether company political connectedness can create wealth for shareholders

- The impact of the political executive’s orientation or the phase of the electoral cycle on stock market movements

- The stock market impact of politically relevant events, such as wars, coups or assassinations

- The impact of domestic political turmoil on stock markets

Stock price movements reflect investor forecasts. Stock price increases imply that investors expect higher public company profits, lower interest rates, or both (lower interest rates mean that future profits of a given size are more valuable). Stock price decreases imply the reverse: lower future profits, higher interest rates, or both. Higher interest rates can indicate that investors see more attractive investment alternatives (and are demanding greater returns from their current investments) or greater risk (and are demanding greater returns to compensate them for their increased risk).

For each of the political situation and event categories the question is whether the political stimulus influences investor expectations about company (or stock market-wide) profits and interest rates.

Company political connections

The first category makes the link between political stimulus and company profits very directly. Researchers have considered several different mechanisms of political connectedness – campaign contributions, elected politician representation on company boards (!) or in the shareholder group, and the participation of company officers in government.

Political connections might affect profits through any of many channels: preferential treatment from government-owned or -influenced companies like banks, lower tax rates, government contracts, regulatory bias, etc. In addition, the political connections may extract some or all the benefit in bribes or political contributions, making the impact more difficult to detect.

According to Wisniewski, assessing of the impact of political connections on the profits of connected firms is difficult. The standard analytical method asks whether the profits of connected firms are larger than the profits of unconnected firms. In effect, we are asking how much profit the connected firms would have earned if they weren’t connected, using unconnected firms’ profits to estimate that. Sounds simple, right?

Even if corporations do benefit, proving it is harder than it sounds. The analyst must:

- Determine what constitutes “connection”

- Ensure that all relevant political connections are captured in the data – difficult because company financial reports tend not to report political connections, and political databases tend not to report company connections

- Match connection time periods with financial reporting periods

- Make statistical adjustments to compare connected and unconnected firms

It’s a lot of work! One paper assembled a database of more than 20,000 public companies in 47 countries and cross-referenced it to country-specific websites listing members of government and legislative bodies.

Despite the analytical difficulties, the evidence confirms that companies get what they pay for either in campaign contributions or in board participation of politicians.

The British study finds that news of the election of a large shareholder or a company officer to government has an immediate impact on the stock price. Investors believe that company participation either in the legislature or in the executive will literally pay dividends for the company, with much larger impact if:

- The country suffers more from corruption according to an independent index (4% vs 0%)

- The company participant is a large shareholder (owner) rather than an officer (4.5% vs 2%)

- The company participant is becoming a government minister rather than simply a member of parliament (12% vs 1%)

In Thailand in the ‘80s through the 2000s, share prices of politically connected companies outperformed the rest by anywhere from .2% to 1.1% per month (2.5% to 12% per year). After the elections of 2001, companies owned by cabinet members outperformed the rest by more than 50% per year (!).

Analysts have also made clever use of surprise political events to estimate the value that investors placed on company relationships with elected officials. Examples include relationships with:

- Suharto in Indonesia (as much as 23% of company value).

- Scoop Jackson (constituent companies lost market value) and Sam Nunn (constituent companies gained market value) after Jackson’s untimely death followed by Nunn filling Jackson’s role on the Senate Armed Services Committee.

Corporate campaign contributions also appear to contribute to company value in the US, despite the legal restriction that contributions can’t represent a quid pro quo exchange with a politician:

- Companies contributing to Republicans suffered value declines of .33% per $100,000 contributed, while companies contributing to Democrats gained .17% per $100,000 contributed immediately after Senator James Jeffords switched from the Republican Party to the Democratic, placing control of the Senate in Democratic hands.

- After the 2000 election, Bush contributing companies enjoyed enhanced stock returns, while Gore contributing firms suffered losses.

In summary, companies (and their shareholders) can gain significantly from their political connections, even in countries such as ours that strive to limit these sorts of benefits.

Leadership politics and stock market returns

In my letter from just before President Trump’s election in 2016, I indicated (and still believe) that there is no strong evidence of causation, even though there was (and is) some evidence that stock market performance has been better under Democratic presidents than under Republicans. That is, the performance differences appear to me to be coincidental.

Wisniewski (remember him?) reviews several analyses of the US data and is forced to say that the existing scholarship suggests that the market performs better under Democratic presidents. I don’t find this surprising – every paper examines data from the same period.

However, he also cites a paper (he is too modest to admit coauthorship in the article text) that analyzes data from 24 countries (including the US) over 25 years (history is shorter for some countries). The authors are looking for evidence of better stock market performance under left-wing than under right-wing governments, or that news of the election of one or the other moves stock markets, or both. They have 180,000 days of stock market performance under 173 different governments, roughly half right-wing and half left-wing.

They find … nothing.

Across the sample, the elections produce no impact on stock returns. That is, looking at returns starting 10 days before the election and continuing 10 days after the election, the stock market shows no interest in which party wins. Average returns are just about flat whether the left-wing or right-wing is going to take power.

In some countries, stock market returns are greater when left-wing governments are in charge, while in others they are higher under right-wing governments. Across the sample, however, the average annual return is .34% (about 1/3 %) higher when the left-wing is in charge, and the advantage is not statistically significant. For the US specifically, in the sample covered by the paper, performance under left-wing governments (the Democrats) is 7.7% per year higher, but this is not abnormally large when considering the full group of countries in the study and is offset by other countries where the reverse is true. In short, the statistics say that the Democratic advantage in the US is likely due to chance.

Does this mean that policies don’t matter? No, it simply means that who is in charge doesn’t provide sufficiently specific information about which policies are implemented and how long they are in force. Governments propose many policies, but usually enact only a relative few, leaving intact most policies of their predecessors. Simply knowing that a government is right-wing or left-wing tells us only that they have policy preferences, not which policies that government enacts (or previous policies they dismantle).

It is difficult to tease out any single specific policy’s economic impact from stock market data or any economic data. If it were easy, we wouldn’t need so many economists! It shouldn’t surprise us that determining the impact of which party is in power is even harder.

The impact of political events

Stock markets don’t like war and international crises more generally, as an exhaustive analysis (nearly 90 years of monthly stock return data for 19 countries and world crisis information on more than 400 crises) demonstrates. The database this work uses defines crisis as follows:

“A foreign policy crisis, that is, a crisis for an individual state, is a situation with three necessary and sufficient conditions deriving from a change in the state’s internal or external environment. All three conditions are perceptions held by the highest-level decision makers of the state actor concerned: 1) a threat to one or more basic values, along with 2) an awareness of finite time for response to the value threat, and 3) a heightened probability of involvement in military hostilities.”

While the paper provides many results, the clearest and most straightforward is that world stock returns are lower by as much as .12% per month or 1.44% per year for each crisis that is underway. On average, there are about 2.5 crises active each month, implying returns lower by .3% per month or 3.6% per year.

Investors worry about the threats to lives, property, and stability that crises bring. They expect lower future profits for their public company investments, and stock markets reflect those expectations.

In addition, stock market volatility increases when crises start, and declines when crises end. These effects are magnified when the crisis in question is a war, or a great power is involved.

Domestic political turmoil

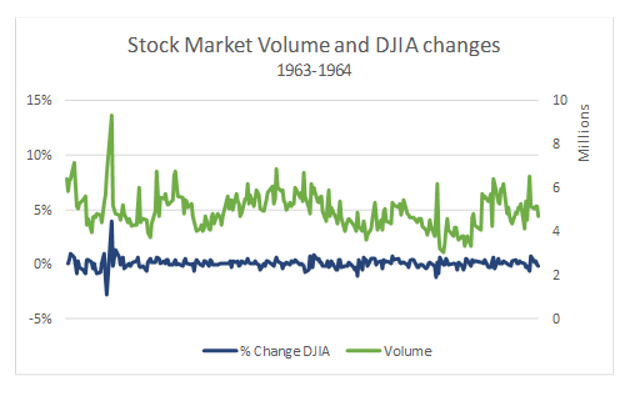

Political assassinations unsettle stock markets, but the long-term impacts depend on what follows. For example, I have graphed daily percentage changes in the Dow Jones Industrial Average (left axis) and stock market volume in shares traded per day (right axis) for parts of 1963 and 1964. See if you can find the Kennedy assassination on the graph. I’ll wait.

You are right! It’s about 10% across the graph from the left – market volume spikes to about 9 million shares, and the market drops about 2.5%, then recovers the next day by about 4%. Presumably, while the assassination of JFK was a major psychological shock to many US citizens (for example, I still remember how upset I was – at the age of 9! – and how upset my parents were), after a day or two of analysis, US investors did not anticipate significant financial effects.

Of course, other unexpected transitions of power such as coups d’état can have more significant effects. Several investigators have observed that companies connected to those gaining or losing power via a coup can enjoy positive returns or suffer negative ones, respectively, as a result of the regime change. These effects are especially large for previously nationalized firms which stand to regain independence.

There is also evidence of a negative correlation between domestic economic uncertainty and stock market volatility. That is, greater uncertainty about government economic policies (measured by news coverage, upcoming tax code expiration, and economic forecaster disagreement about future inflation and government spending) is linked both to more day-to-day variability in stock returns and to higher expectations for future volatility.

Conclusion

First, it’s clear that political events do affect the stock market. We’ve seen many examples. Indeed, if the events are likely to affect company profitability, they will affect stock market returns.

Second, the sizes of the investment impacts relate to the anticipated effects of the events on the profitability of companies – international crises and war lead to the destruction of property and deaths –catastrophic events. Peaceful changes in political leadership can change the prospects of individual companies connected with entering or departing leaders, but there is no suggestion that such changes have predictable effects on the performance of the entire stock market.

Finally, while domestic political turmoil and economic policy uncertainty can increase stock market volatility, we would expect direct effects on returns to be limited.

What does this say about the likely portfolio effect of the upcoming election?

- Do expect more day-to-day stock market volatility.

- Do expect differences in:

- Trade policy

- Immigration policy

- Climate policy

- Regulation in both environmental impact and financial services

- Add your favorites to the list

- Don’t expect predictable effects on stock or bond returns broadly.

While we are not recommending portfolio adjustments at this time, you may wish to respond to the likely increase in stock market volatility. If so, please be in touch with your advisor.