If you know anything about Sensible Financial Planning, you are probably familiar with Treasury Inflation Protected Securities or TIPS. We’ve written extensively on the subject, produced numerous webinars and frequently build TIPS ladders for clients (a bond ladder is a series of bonds that matures in different years).

Despite advising clients on TIPS for more than a decade, I never owned a TIPS until last January when I purchased ~$10k worth at auction. I hoped that the experience might provide a learning opportunity and useful material for a future article.

If you own TIPS (either funds or individual bonds) or are interested in them and would like to know more about how they keep pace with inflation and how to understand returns, then continue reading. Going beyond the theory, I will attempt to clarify some of the confusing aspects of TIPS ownership, such as why my bonds are guaranteed to keep pace with inflation but show an almost 0% return after a year.

Because TIPS are tricky, I’ll start with a more traditional bond example and then explain how TIPS differ. In the first two sections I’ll briefly explain what a bond is and some of the factors that complicate calculating bond returns. You can skip these sections if you’ve read my articles on bonds here and here. In the last section, I will show how your custodian’s performance information is misleading and how to calculate TIPS’ actual returns.

What is a bond?

A bond is simply a loan to a company or a government. In exchange for this loan, the bond issuer promises to repay the loan at maturity and pay the investor interest over time. When the issuer is the US government, the loan is called a Treasury bond. (TIPS are a special type of Treasury bond). Treasuries are typically issued with maturities of 5, 10, 20 or 30 years. Treasuries pay interest semiannually in the form of “coupons”. When the bond matures, the investor receives their initial loan (principal) back. We can illustrate this arrangement with a simple example.

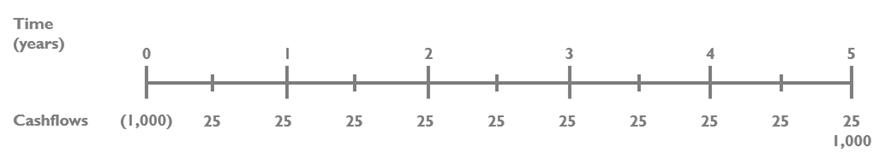

Assume I purchase a five-year Treasury bond for $1,000. The interest, or coupon, rate is 5%. The life of my Treasury looks like the following:

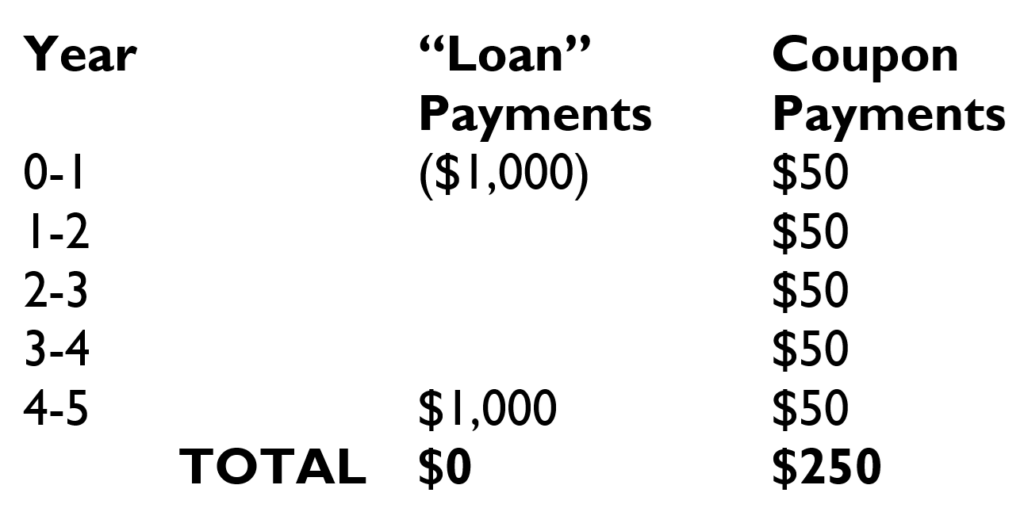

When I purchase the bond (Time = 0), I lend the government $1,000, shown above as a negative number. In bond language, the bond has a principal value of $1,000. This is both the purchase price of the bond and the amount that the government promises to repay at the end of five years. You might also see face value or par value. The coupon rate is 5%, and since Treasury bonds pay semiannually, this means I will receive a $25 coupon every six months. I will continue to receive a $25 coupon every six months until my bond matures (Time = 5), when I receive my final coupon payment plus the principal of $1,000. We can summarize all the transactions in a table:

The table illustrates what happens when an investor buys a bond and holds it to maturity. The bond is a loan (Loan Payments column) with interest (Coupon Payments column). This brings me to my first point about bonds:

If held to maturity, all (or nearly all) of a bond’s gains are due to interest (or coupon) payments.

You might think that determining a bond’s return would be simple, i.e. just add up all the coupons. But performance is complicated by certain risk factors.

What factors affect bond returns?

The example above serves as a useful illustration, but real-world investing involves risk. The following three risks could lead to different results:

- The issuer defaults or pays back less than promised (default risk).

- The bond is sold prior to maturity, and interest rates have changed since the purchase date (interest rate risk).

- Inflation reduces the “real” (inflation-adjusted) value of bond payments (inflation risk).

I’ve previously written about bond returns here and here. I recommend you read those articles if you haven’t already. But for the purpose of this article, which focuses on TIPS, I will summarize these risks and how they impact TIPS returns.

First, because the U.S. federal government issues TIPS, default risk is extremely low. In fact, relative to other investments, a U.S. Treasury Bond is considered the safest investment in the world. We can assume that the default risk is as close to zero as possible, so default risk does not impact TIPS returns.

On the other hand, interest rate risk does impact TIPS returns. If rates increase after an investor buys a bond, the price of that bond will decrease. This happens because new bonds are issued with higher interest rates, making the older bonds with lower rates less attractive. This brings me to my second important point about bonds.

If an investor sells a bond prior to maturity, they could realize a loss if interest rates have increased since their initial purchase.

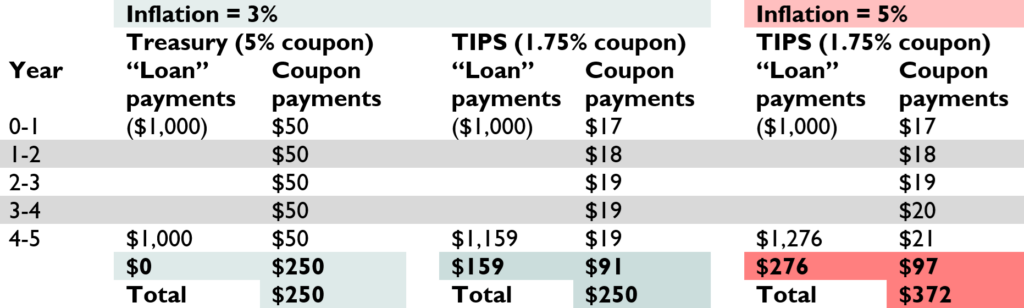

Inflation is another risk to consider with bonds. Returning to my Treasury example again, let’s assume that inflation in one hypothetical 5-year period is 3% per year and in another is 5%. While I receive the same coupon payments and principal repayment, I am wors off if inflation is 5%. My interest payments and return of principal are worth less in real dollars (purchasing power) because of higher inflation. Inflation is a serious risk for most investments. This is where TIPS stand out.

How do TIPS differ from traditional bonds?

TIPS are special. While nearly all bonds pay in nominal (unadjusted for inflation) dollars, TIPS pay in real dollars. How does this work? TIPS pay coupons just like nominal Treasuries, but the principal value, known as the adjusted principal, increases over time with CPI. This means that both the loan (principal) and interest (coupon) payments keep pace with inflation.

If inflation is normal, the Treasury and the TIPS perform the same. However, if inflation is higher than expected and is 5% over five years, the TIPS performs substantially better than the Treasury. While the coupon payments are less than the Treasury’s, the inflation-protected principal adds significantly to the bond’s total return, resulting in an almost 50% higher total return!

Knowing how TIPS work and how their performance can be affected by certain risks, I will turn to my TIPS to explain how to calculate performance.

What is going on with Frank’s TIPS?

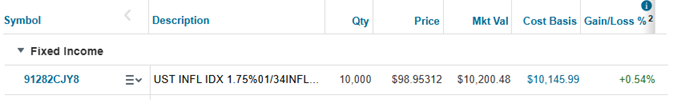

I have a problem. I bought my TIPS over a year ago, and while inflation has been just over 3%, my bond only shows a gain of 0.54%. Why hasn’t my bond kept pace with inflation? Let’s take a look at my bond’s statistics from Charles Schwab’s website to try to understand what is going on.

Let me first explain the above table:

- Symbol. The bond’s CUSIP. This is a unique identifier, like a person’s social security number.

- Description. This is a United States Treasury (“UST”) bond which is indexed to inflation (“INFL IDX”). It pays a 1.75% coupon and matures in January of 2034 (“1/34”).

- Qty. Number of bonds purchased.

- Price. What I originally paid for the bonds or $98.95 per TIPS.

- Mkt Val. What I could sell my bonds for today.

- Cost Basis. This is the bonds’ adjusted principal (more on that below).

- Gain/Loss %. The percentage of gain/loss based on the difference between the Mkt Val and the Cost Basis.

Schwab and I have a disagreement as to my bond’s gain/loss. Like most custodians, Schwab calculates my gain/loss in terms of price change only. To calculate my holding period return (“HPR”) – my total return from the purchase date through today – I need to do some math. Bond returns come in two forms, income return and price return. I’ll first calculate the return due to income and then the price return.

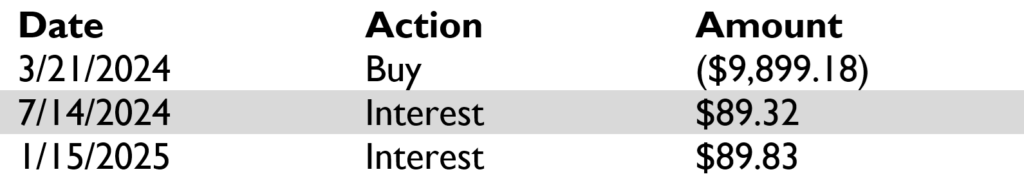

My coupon payments do not show up in Schwab’s Gain/Loss% calculation. To calculate my income return, I review my transaction history where I see the following:

Since making my initial loan of $9,899.18 I have already received $179.15 in coupon payments. We can calculate this gain as follows: (179.15)/(9,899.18) = 1.81%. This is already quite a lot higher than the 0.54% that Schwab reports. The table also shows that my coupon payments are paying a real interest rate. The January 2025 coupon is higher than the July 2024 coupon by CPI.

Next, I need to calculate the price return on my investment. We can use the following formula:

Gain/Loss (%) = (current value) / (cost basis) – 1

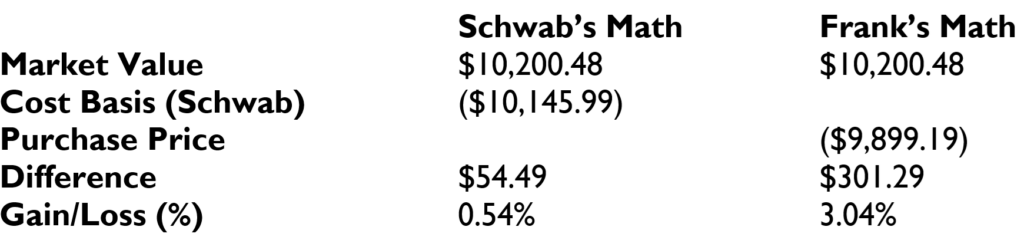

Cost basis refers to the amount someone pays for an investment. But for TIPS, most custodians report cost basis as the bond’s adjusted principal. Recall from above that this is the purchase price of the bonds adjusted over time by inflation. Were I to sell my TIPS today, the gain according to Schwab would be the difference between the market value, $10,200.48, and Schwab’s “Cost Basis”. But if I substitute “Cost Basis” with my original purchase price, I get a much higher gain. Here are the two calculations side by side:

So which calculation is correct? They both are, but for different purposes. Schwab’s gain/loss shows my taxable gain were I to sell my bond today. Using the bond’s adjusted principal is appropriate because as the principal increases with inflation, I am taxed on the increase whether I sell the bond or not. But if I actually sell the bond, I would only owe taxes on the difference between what I receive (market value) and my tax basis (adjusted principal).

However, if I want to calculate my investment return, then we should us my math, which shows a price return of 3.04%.

Now that I have separately calculated my income and price return, I can calculate my bond’s holding period return:

HPR = income return + price return

= 1.81% + 3.04%

= 4.85%

We can see that my bonds have performed very close to what I expected. 1.81% in interest payments plus an increase in price which very closely matches inflation over the period. I’m actually slightly ahead of what I expected, as the market value of my bond somewhat exceeds the adjusted principal. (The reverse could have also been true had real interest rates increased since I bought my bond). So importantly, my bond’s price does fluctuate with interest rates. But if I hold my bond until it matures in January of 2034, I will receive exactly what I expected in real dollars both in terms of my 1.75% coupon payments and the inflation-adjusted return of my original loan.

Therefore, despite appearances, and Schwab’s math, inflation is up, and so are my TIPS!

In conclusion

In general, custodians do not report a bond’s total return. The gain/loss investors see on their statements can be quite misleading if we confuse taxable gain/loss with investment, or holding period, gain/loss.

We can calculate a bond’s holding period return by adding up the income return (the sum of all coupon payments) and its price return. Only after making the necessary adjustments do we really know how our bonds have performed over some period.

Photo courtesy of Joshua Mayo on Unsplash