In my previous two articles, Understanding Bond Returns and How Does Inflation Affect Bond Returns?, I attempted to explain why bond prices behave the way they do. First, I showed that bond returns are two-fold: income return (by far the largest part of a bond’s return for the long-term investor) and capital return. Second, I showed how the discounting process is used to calculate the value of a bond. Third, I showed how three factors, credit, interest rates, and inflation, can impact bond values. In this article I will show that rising rates, even when they severely negatively impact bond prices, actually improve most long-term investors’ financial situations.

Long-term investors benefit from higher rates

The above statement may be somewhat less than comforting if today, in September of 2022, you open your statement and look at your bond portfolio’s performance. Many bond funds have lost more than 10% year-to-date. Nevertheless, it’s true. Higher rates are a long-term investor’s friend.

Imagine two hypothetical retirees where everything is equal except the rates they receive on certificates of deposit. Retiree 1 can invest in CDs which yield 5%. The CD yield for Retiree 2, however, is only 1%. Retirement is much less expensive for Retiree 1. This observation strikes most people as intuitive — higher savings rates make for a less expensive retirement. But after the losses we’ve seen in bonds recently, primarily due to rising rates, are investors truly better off today than they were a year ago? I will answer that question from two perspectives. Note: bond losses due to credit and changes to inflation are different types of losses, which I covered previously. In this article I will only focus on losses that result from changes to interest rates.

In the long run, the return on a risk-free bond is almost all yield

In my first article in this series, Understanding Bond Returns, I proposed the following formula to understand bond returns:

Bond Total Return (%) = Coupon Rate (%) + Change in Price (%)

In a year like 2022, the change due to price is so large that it almost completely swamps bonds’ total returns. If bond prices decline 12% and coupon payments are 1%, then total return would be -11%.

But over the long-run, price fluctuations have a small impact on the performance of risk-free bonds. Imagine this simple hypothetical. You purchase a Treasury bond at auction and hold it until maturity. While the price of that bond fluctuates from when you purchased it to when the bond matures, at the end of the holding period your return is all income. A bond index fund, which is simply a collection of hundreds or even thousands of bonds, will behave similarly.

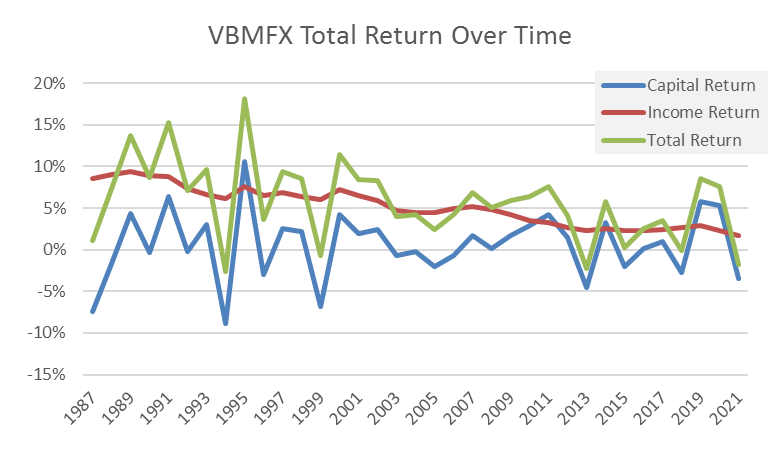

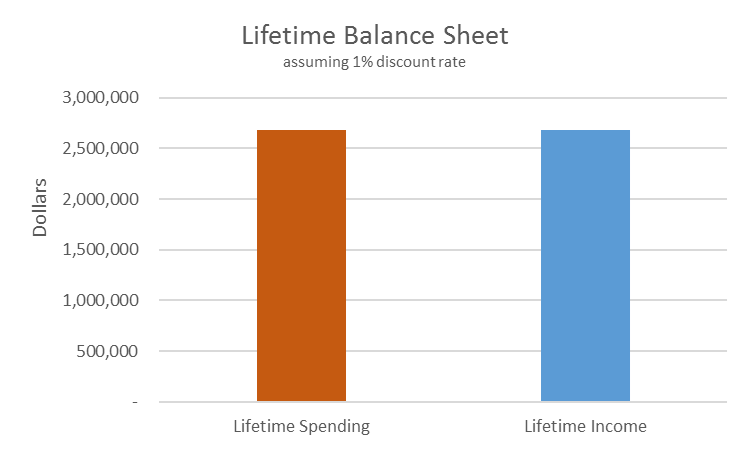

Take for example Vanguard’s Total Bond Market Index mutual fund (VBMFX), basically the U.S. investment-grade bond market. This is a good fund to use as an example for two reasons. One, the fund is very old, going all the way back to 1986, so we have lots of history from which to draw conclusions. Two, Vanguard’s website provides detailed performance information. In my experience investors only see bond total return, but Vanguard’s website breaks down total return into capital and income return.

Data provided by Vanguard shows VMBFX’s performances since 1987. Return is shown in terms of capital (price), income and the sum of the two total return.

The performance data from 1/1/1987 through 12/31/2021 lets us calculate annualized return and cumulative return, broken down into its components.

You can see how Total Return is almost completely explained by Income Return. Investment-grade bonds certainly experienced price fluctuations since 1987, see the blue line in the chart, but a whopping 90% of long-term bond returns is explained by income return or yield. And if yields fundamentally drive bond returns, and investors benefit from higher yield, then it follows that rising rates are the long-term investors’ friend.

But haven’t 2022’s large bond price declines been bad for investors? An investor who put all their financial assets into VBFMX, or a similar bond fund, would have seen their savings decline roughly 12% year-to-date. So rising rates might be better in the long run, but in the short run it certainly feels like 2022 has led to substantial losses for bondholders. There’s a more holistic way to view the recent rise in rates that further supports the argument that bondholders are in better financial shape today than a year ago.

For most investors, rising rates lower lifetime spending by more than lifetime assets leading to better financial outcomes

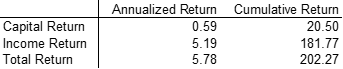

Imagine a very simple financial plan. A retired, 70-year-old individual planning to live to age 100 has estimated annual expenses of one-hundred-thousand dollars per year and owns one asset, a bond portfolio.

The orange bars below represent annual spending of one-hundred thousand dollars per year through age one hundred. The blue bars are the client’s bond portfolio. To simplify things, I am using “real” or inflation-adjusted cash flows (spending for example is level versus sloping upward) and zero-coupon bonds (a special type of bond that does not pay coupons).

In the example, the client owns a ten-year bond ladder with two-hundred-seventy-five thousand dollars in (real) bonds maturing every year. I chose a 10-year bond ladder because the average age of the bonds in the ladder is very similar to that of VBMFX, something individual investors might own.

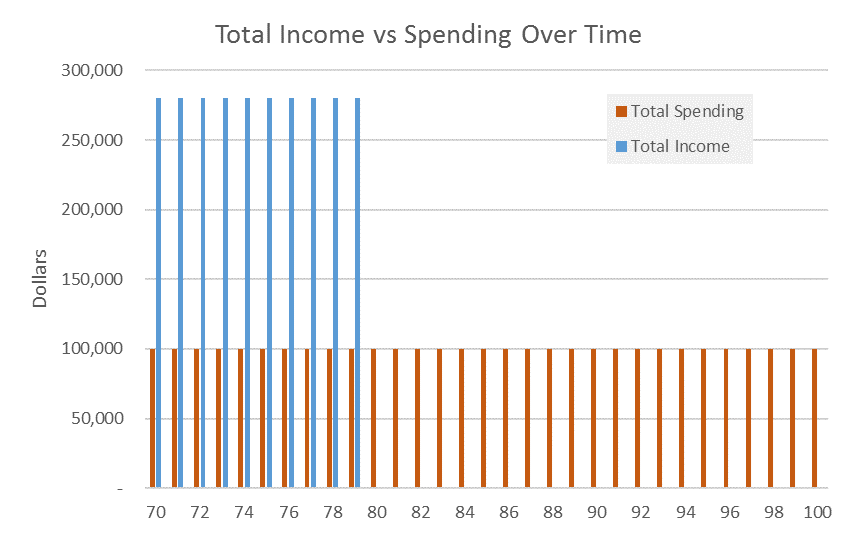

You may recall from my previous article, Understanding Bond Returns, that we use a process called discounting to calculate the value of a bond based on its future cash flows. We can do the same for a portfolio of bonds to determine what value or price a bond portfolio is worth. Using a discount rate of 1% real, the value of the above bond portfolio is $2.6 million. Put another way, our hypothetical investor could buy the above bond portfolio for $2.6 million.

We can use discounting again to calculate the value of the individual’s estimated lifetime spending. Discounting one-hundred thousand dollars per year through age 100 results in lifetime spending of $2.6 million. Total lifetime spending equals total lifetime assets! This is no accident. I picked numbers that would produce this result.

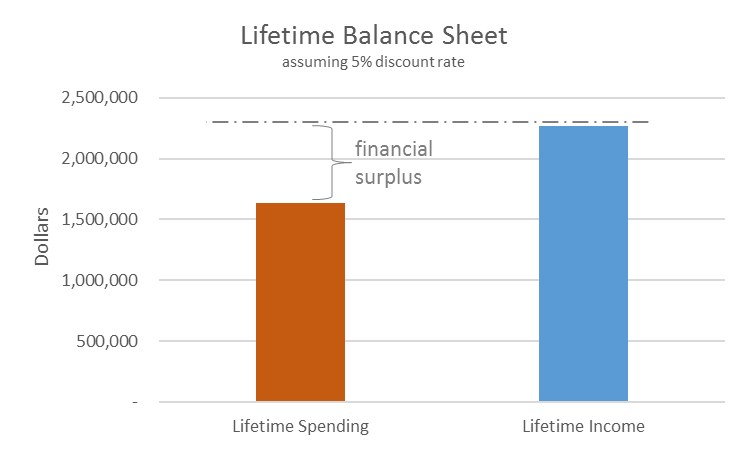

We can visualize this investor’s simplified financial plan as a lifetime balance sheet.

From a financial planning perspective, we would say that this person is living within their means. This plan “works” because lifetime assets are sufficient to cover lifetime spending. But what if rates rise, as they have recently, to something above 1%? What if real rates rise 4%? (This is a greater increase than recent history but I want to illustrate an extreme example). Were this to happen, we would increase the rate we use to discount cash flows to 5% (1% plus a 4% increase) and recalculate lifetime spending and income.

Using the same projected cash flows with our new discount rate, we recalculate the individual’s bond portfolio as $2.27M. That is a decline of almost 13%! Recall these are investment-grade, read “safe”, bonds and this person has just experienced a double-digit loss in her lifetime savings. But this is only one half of the story. We need to recalculate her lifetime spending to assess whether this financial plan still works.

Discounting the same one-hundred thousand dollars per year for life using a 5% rate leads to a new lifetime spending number of $1.64 million. Both lifetime spending and income are lower with higher rates, but our hypothetical investor is (much) better off. Instead of a financial plan where lifetime income equals lifetime spending, lifetime income now exceeds lifetime spending resulting in a financial surplus of over six-hundred thousand dollars:

Rising rates are indeed a long-term investor’s friend, even when they result in lower bond prices. Because our investor’s expenses extend far beyond the bond ladder, rising rates lead to larger declines in total spending versus total income which in turn improves financial plans.

This does not mean that all price declines for bonds are a good thing. Declines due to changes in credit or changes to expected inflation are losses that do not reduce lifetime spending. Furthermore, not all increases in rates lead to better outcomes. In the above example, our investor’s lifetime spending extends far beyond that of her bond portfolio. An investor at an advanced age, say 95, whose bonds mature well past her expected lifespan would experience an economic loss were rates to increase. For these reasons it is important to understand what types of bonds you own (are they subject to credit or inflation risk?) and whether the bonds you own are appropriate given your investment time horizon (do they mature before you plan on spending the proceeds?).

As always if you have any questions or if you would like to discuss your investment portfolio in detail schedule a meeting with your advisor and we will be happy to answer any questions or concerns you may have.