International trade, and especially US international trade deficits, have been a large part of the news recently. President Trump has seized on trade deficits and the impact of globalization on US jobs and US businesses as central political issues.

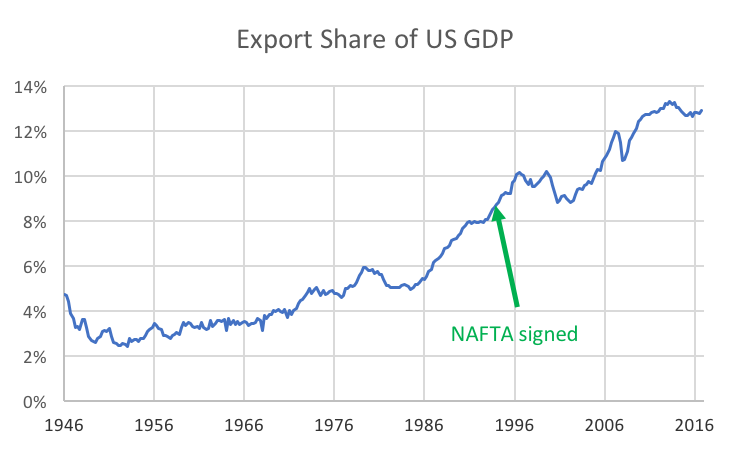

International trade plays an increasingly important role in the US economy. The chart above shows exports growing from 3% or 4% of the economy right after World War II to roughly 13% last year. Today, one of every eight dollars worth of the products we make, the food we grow, and the services we deliver represents revenue from a foreign buyer.[1] The chart also suggests that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was part of a trend rather than an isolated event.

International trade plays an increasingly important role in the US economy. The chart above shows exports growing from 3% or 4% of the economy right after World War II to roughly 13% last year. Today, one of every eight dollars worth of the products we make, the food we grow, and the services we deliver represents revenue from a foreign buyer.[1] The chart also suggests that the North American Free Trade Agreement (NAFTA) was part of a trend rather than an isolated event.

International trade is even more important from a global perspective: in 2016, world GDP was just shy of $76T (that’s 76 trillion dollars).[2] World exports were about $20T,[3] or 26% of world GDP. One of every 4 units of value of the products, food and services produced in the world was delivered to a buyer in a country foreign to the maker, grower or provider.

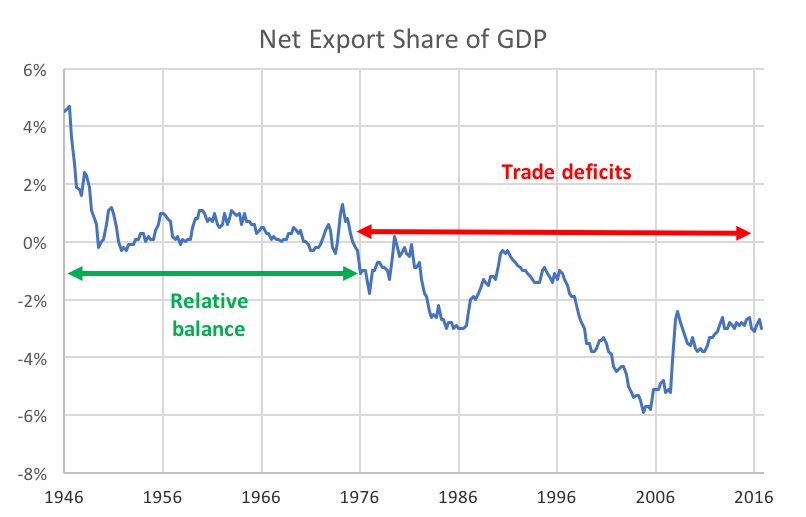

From the end of World War II until the mid-1970s, US international trade was in balance or in surplus. Since the mid-1970s, however, our international trade, in the current account, has been in deficit.

When discussing international trade, a little bit of terminology goes a long way. Economists measure international trade using two accounts:

- The current account captures trade in goods and services.

- The capital account summarizes trade in real and financial assets.

When people talk about international trade and especially when they are talking about the trade deficit, they are talking about the current account.

Combined, the current account and the capital account must be in balance. As a simple example, suppose that you buy an iPhone from China for $1,000, and suppose that is the only international trade for the US with China in the year. The US would have a current account deficit of $1,000 with China (we’d have bought $1,000 worth of iPhones, and China would have bought no goods and services), and a $1,000 capital account surplus with China (we’d have “sold” them $1,000 in US dollars, and we would have “bought” no Chinese renminbi). Or equivalently, China could use its $1,000 in cash to buy Treasury bonds, or stock in Apple, say. The US would still have a $1,000 capital account surplus with China (bonds and stock are financial assets).

Alternatively, China could use its $1,000 to buy fertilizer from Malaysia, so China would have no surplus in either its current or capital account overall (in effect, it traded an iPhone for fertilizer), but it would have a current account surplus and capital account deficit with the US and a current account deficit and capital account surplus with Malaysia.

Overall, each country, including the US, must have its total international trade balance (current account plus capital account) equal to zero, neither in deficit nor in surplus. It’s trade, after all, not theft. If the current account is in balance by itself, we are selling an equal value of goods and services to foreign buyers as we are buying from foreign sellers. If the current account is in deficit, we are trading some financial or real assets (stocks, bonds or real estate) for goods and services.

So, who cares about the (current account) trade deficit?

Domestic companies and individuals who compete with foreign providers in producing goods and services care, a lot. They see imports as sales they could have had, and argue that imports cost them business and profits. They see themselves as losers. And, importantly, the losers know each other – business owners associate at conferences, and workers work together. This makes it easy for them to communicate their unhappiness in a coordinated way, both to the government and to the press.

On the other hand, consumers and importers are happy with imports. They like to be able to choose foreign-produced goods and services if they offer better deals than comparable US-produced goods and services. Unlike the losers, however, consumers don’t associate with each other around these better deals. They aren’t well positioned to advocate for themselves as a group.

Domestic companies who oppose imports ask the government to protect them by making imports more expensive. If the companies have enough political power, governments respond by imposing tariffs (taxes on imports). With tariffs, the government forces those who would buy imported products and services to pay more for them, effectively making it easier for domestic producers to compete.

In the economist’s ideal world, international trade extends the benefits of competition beyond national borders. Companies and countries sell and deliver products and services in which they have comparative advantage, and consumers buy and receive the collection of goods and services they prefer at the lowest total cost. Global competitive product and service markets work efficiently to make all of us better off.

In addition, many imports serve as components of domestically produced goods and services. Imported components represent positive “downstream effects” of international trade. The US car industry provides an excellent example. If you’ve bought a car recently, you know that all domestic cars contain parts made in foreign countries. The US and Canadian industries are so tightly integrated that National Highway Traffic Safety Agency (NHTSA) reports on the sources of car content by country don’t even attempt to distinguish between US and Canadian content. Further, even the domestic cars with the highest percentage of US and Canadian content have nearly 30% of parts by value coming from other countries. Clearly, both US car manufacturers and their customers know that imported parts make US cars less expensive. Equally clearly, tariffs on imported parts would tend to make US cars more expensive (these would be negative “downstream effects” of tariffs).

Now that I’m a recovering economist, I understand better that the world often doesn’t function consistently with economists’ models. The conditions required for perfect competition rarely obtain. Nevertheless, even after accounting for deviations from perfection, an overwhelming majority of economists believe that international trade is good, and that tariffs are bad.[4]

Let’s look at a few of the arguments against free trade and for tariffs before we close.

- “Unfair” subsidies. Not all countries play fair in international trade. Some subsidize domestic companies in “special” or “strategic” industries. Subsidies, or payments from the government, reduce net costs, and allow the companies receiving the subsidies to sell abroad at lower prices.

- Economists ask, why prevent a foreign government from paying subsidies that our consumers benefit from? These are effectively gifts from the foreign government to us. If domestic workers are displaced, they can find another productive job, and domestic companies that lose business can shift their capital elsewhere.

- The displaced workers and domestic companies that lose business are still unhappy, though. Government responses can include (in decreasing order of benefit to the domestic economy):

- Helping displaced workers and companies move to another area of the economy where they can be productive again;

- Working through established arrangements (like the World Trade Organization or WTO) to reduce or end the subsidies;

- Negotiating with the foreign government to halt the subsidies (a strategy complicated by the fact that the subsidized companies likely have considerable political power – that’s why they are getting subsidies!);

- Imposing tariffs (countervailing duties) on the subsidized imports.

- “Dumping.” Like subsidies, dumping is sale of products or services in foreign markets at prices below cost.

- The analysis of dumping is very similar to that for subsidies, and so are the solutions.

- Infant industry. In a developing country, an industry for which the country is well-suited may not yet exist, or may be immature. Importing that industry’s product may prevent the domestic industry from ever developing.

- Tariffs on imports may allow the infant industry to develop. Deciding when the industry is mature enough to compete without tariff protection is likely to be politically fraught.

- National security. Certain industries are so important for national security that we must ensure that they survive and prosper. Tariffs will protect them.

- Many economic capabilities are shared among allies. Efficient production makes the alliance stronger.

- Tariffs to protect domestic industries promote inefficient production and reduce GDP.

- Accepting the national security argument encourages all trade losers to identify themselves as “critical to national security,” and deserving of tariff protection. “National security” reveals itself as a political question rather than one of military supply.

- Mercantilism. This version of economic nationalism was popular among European nations in the 1500s and 1600s. The notion was to maximize exports and minimize imports, thus increasing the domestic stocks of gold and silver (the money of the day). The question begged is “then what?” What are the gold and silver to be used for? The answer then was, frequently, to wage war. Gold and silver hired troops and weapons, and countries that had paid for imports with gold and silver had fewer resources to wage war.

- Most economists now view mercantilism and economic nationalism as largely discredited:

- Manufacturers and agricultural magnates were mercantilism’s winners. They benefitted most directly from tariffs and limiting exports.

- Consumers (most of the population) were losers.

- Mutually beneficial trade unlocks very significant specialization benefits – for example, there are good economic reasons that English wine is not well known, and similarly for Italian oil (petroleum, not olive!).

- Most economists now view mercantilism and economic nationalism as largely discredited:

Linking the discussion above directly to the current political debate: the behavior of the Chinese government with respect to its domestic companies is mercantilist. The owners of many of these companies have strong government ties. Limitations on foreign ownership and demands that these companies receive free access to foreign technology are efforts to increase the wealth of the owners. Chinese workers and consumers will receive little benefit (and may even lose to the extent that foreign owners might increase the efficiency of the companies). Imposing higher tariffs on Chinese goods forces American consumers to pay higher prices so that Chinese consumers and US capital owners can benefit. (On the other hand, if the threat of tariffs causes the Chinese government to lift the limitations on foreign ownership and revoke the demands for technology transfer, then the benefits accrue without cost to US consumers.)

And finally, a very brief example of tariffs and trade wars. In 1930, despite the concerted opposition of many economists, [5] the US Congress passed and President Hoover signed into law the so-called Smoot-Hawley Tariff, which raised US tariffs on a very large number of imported goods. Many countries retaliated by raising their tariffs, and world trade declined sharply (a recent estimate is that international trade declined by a third from 1929 to 1932, and over half of the decline was due to the Smoot-Hawley tariff and the ensuing trade war[6]).

In summary:

- International trade is a good thing, enabling production to move to its most efficient locations.

- The benefits of international trade are not distributed evenly.

- The many winners are diffuse, and receive small benefits per person.

- The losers are concentrated, and their per person losses can be large.

- Trade’s losers agitate to be protected.

- Tariffs are expensive protection.

- They reduce the volume of international trade.

- They retard the movement of economic activity to its most efficient locations.

- Direct responses to the losers can be more helpful.

- Compensation, and help in moving to more productive situations.

- Direct action (negotiation, cooperation with similarly affected trading partners and trade organizations) to prevent “cheating” by foreign companies and countries.

- Tariffs are expensive protection.

If the President’s proposed tariffs are all enacted, it is likely that other countries will enact retaliatory tariffs, and world trade will decline. This would reduce US and world economic growth, and while there would be some US winners, investors broadly are unlikely to be among them.

With that said, predicting the impact on investment portfolios is impossible.[7] We don’t know:

- Which if any of the tariffs will be enacted. The President’s actions and responses to domestic and international political pressure are unpredictable – much of what he says appears to be a negotiating gambit.

- Which countries, products and services will be ultimately affected.

- Which, if any, countries will retaliate and to what extent.

- How significant the political pressure against tariffs will become.

- The size of the impact on investment returns.

- How long the tariffs imbroglio will last.

Diversification is likely to be your best protection as an investor.

Rick Miller is the founder of Sensible Financial Planning and Management. Got a question for Rick about the stock market? Ask in the comments section below, or get in touch with us via email.