Human capital is an essential concept to understand and use when planning for retirement. But what is it, and why does it matter so much? Click here to watch my webinar on human capital.

Human capital is a relatively new idea. It emerged among social scientists in the 1950s from work on economic growth and the economics of education. I was fortunate to study with Gary Becker, who wrote the book Human Capital in 1964. Retirement, as I’ll discuss later in this post, is also a relatively new idea. The earning power of your human capital changes with time and the decisions you make. When and how you retire are some of the biggest financial decisions you’ll make in your lifetime. Learning about this subject will help you prepare for those decisions.

What is human capital?

Human capital consists of your capabilities and knowledge. It is your most productive asset.

Examples of human capital:

Capabilities

- Intellectual skills like reading, writing, and math

- Physical skills like using your body to operate a machine, paint, or play a sport

- Cognitive skills like analysis and planning

Knowledge

- Cultural knowledge like etiquette and social awareness

- Societal knowledge like history and current events

- Specific knowledge like science, culture, or another field of work

The more human capital you have, the more productive you can be. You can increase your human capital by developing skills, like practicing a musical instrument or earning a degree or certification. Your human capital also helps create meaning in your life. In financial planning, we focus on human capital’s earning power.

The value of your human capital

Your human capital is your largest, most reliable, and most valuable asset for much of your life. It directly influences the value of your time as you trade it for goods and services.

Many things affect its value, including:

- How much the market will pay for your knowledge and capabilities: Being more educated or skilled makes your time more valuable to employers.

- Your job’s amenities, risks, and stresses: Easier jobs usually reward you with less compensation, while riskier and more stressful jobs pay more.

- How much time you’re willing to sell: If you earn an hourly wage, working more hours will earn you more money. If you’re salaried, working more will increase your job experience and reputation.

- The region where you work: You will typically earn more in larger cities and more economically productive countries. However, the rise of remote work has disrupted this trend for knowledge workers.

- The company where you work: You may earn more if you change to an employer who values your unique skillset or shift towards a more lucrative field.

- Time: Job experience adds value to your human capital. Some of your skills can depreciate over time. Market trends change the value of certain skills. No one is hiring switchboard operators anymore.

Human capital in your financial plan

The human capital trade-off

You decide how to allocate your human capital. The basic trade-off is how much time you commit to the market. In the short term, that means questions like:

- How much will you invest in your education?

- How much time will you spend at work versus at home?

- How much work stress are you willing to endure?

In the long term, strategizing how to use your human capital means questions like:

- How will you vary the ratio of your commitment to the market over your working life? For example, will you take time off work to raise children or care for your family? Do you plan to take sabbaticals?

- When will you retire? Retiring earlier gives you fewer years to earn a return on your investment. Retiring later gives you fewer years when your time is fully your own.

Taking a lifetime perspective on retirement

Decisions you make today can influence the rest of your life. Which job you take, whether you have children, and how much of your income you save and invest are just a few of the factors that affect your finances in the long term. Sensible uses an accounting concept called the lifetime balance sheet to plan for clients’ entire lives. The lifetime balance sheet helps you keep track of your resources over time and be realistic about your financial options.

Your lifetime balance sheet summarizes your lifetime resources (the assets you will accrue over your lifetime) and your lifetime spending. You can’t spend more than your lifetime resources. Your balance sheet helps estimate how much of a surplus or deficit your financial plan will leave you with.

Your human capital is largest early in your life.

When you first enter the workforce, your human capital is large. Your future earnings are valuable, you have huge potential, and can follow many paths.

Young people have access to resources which increase their human capital:

- Knowledge derived from their education

- A young body with lots of energy

- Familial support like money, belongings, and knowledge

- Societal support including their social network

That adds up to a lot of current and future earning power!

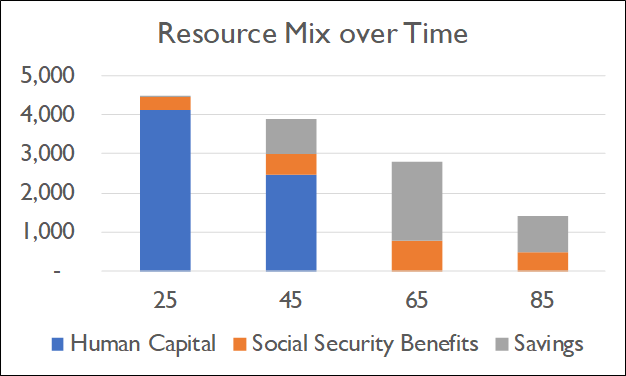

Here’s an example of what someone’s resource mix might look like over their lifetime. This person is earning $150,000 a year from age 25-64, spending $115,000 every year, and earning an interest rate of 2 percent. Their human capital is more than 90 percent of their resources at age 25. Over time, they save money and accrue Social Security benefits as their human capital declines in value. When they retire at 65, their human capital no longer has financial value because they’re not working anymore.

Getting and growing human capital

Your human capital changes over your life. You have a major influence on whether it grows and how. The two main ways you can increase it are education and job experience.

- Education

- General education

- High school

- College “liberal arts”

- Specialized education

- Professional

- Technical

- General education

- Job experience

- Internships

- Job rotations

- Formal training

- Mentorship

- Experience

Maintaining your human capital

Like physical capital, human capital can depreciate. You must maintain it. Even if you do your best to keep your human capital valuable, it can depreciate anyway.

What shrinks your human capital?

- Your knowledge can become less valuable. Travel agents’ skills used to be essential, but these days most people plan and book travel themselves.

- Human capital you lack can become more important. Changing technology can make your human capital obsolete if you don’t add new skills and knowledge.

- What you can do can become less valuable. For example, automation can reduce the value of certain types of human capital.

Being flexible and adaptable is key to shielding your human capital from depreciation. You can’t always predict which of your skills could become obsolete, but if you maintain a wide range of skills and continue to learn throughout your life, your human capital will retain more of its value.

Human capital in your retirement

Retirement is why financial planning exists. When you stop working, you stop earning income. You don’t stop spending, so you need to save and invest so you still have assets to draw on. Because you’re no longer earning, unexpected changes in your spending and assets have a greater effect on you than they would if you were still working. The earlier you retire, the more you must save in advance, and the more exposed you are to investment and inflation risks.

Deciding when to retire

Retirement is a relatively new idea. Before the industrial era, people didn’t retire. They hunted, gathered, and farmed for their whole lives, until they became too old or disabled to work. In the 1800s, nearly 80 percent of men over 65 participated in the labor force. Now, less than 30 percent of men over 65 work. Those who do often choose to work less than they used to. Plus, older adults (85+) have always worked less, and more people are living into their 80s and 90s now.

The earliest schemes for financial support in old age were linked to life expectancy. When the U.S. established Social Security, the average life expectancy was 58. The government set the retirement age at 65 because that seemed fiscally feasible. The idea was to support the people who lived so long they could no longer work. Life expectancy in the U.S. has increased dramatically over the years. In 1900, it was age 47; By 2005, it was 78 — 30 years longer! The expected length of retirement also increased by about 30 percent. Despite this big increase, the Social Security Administration only pushed the “full retirement age” forward by one year.

Social Security has made saving for retirement easier and has a major influence on people’s retirement decisions by strongly suggesting a retirement age.

Retiring and claiming Social Security are independent actions. You can retire at 65 and put off claiming Social Security benefits for years. Social Security benefits increase each year from age 62 to age 70. It can even be beneficial to retire after 65, despite the norm established by Social Security.

Why should you retire?

How do you know when to retire? There are several reasons it might be time:

- You can no longer compete. Younger people have inherent athletic advantages and learn new skills and technology faster. However, older people are taken more seriously in leadership roles and still perform well at knowledge work beyond their 60s.

- It’s dangerous. People in careers that involve physical risk or require rapid reactions in real time such as airline piloting and truck driving might retire because they fear they could put lives at risk. People with dangerous careers may undergo testing to see if they can still do their jobs safely.

- You can’t do it physically. Many kinds of physical labor become harder or even painful over time. A construction worker, dancer, or miner might retire because they’ve developed an illness or disability that makes it impractical to keep working.

- Preference. If you want and can afford to do something else with your time, why not retire?

Why does your human capital shrink after you retire? What can you do about it?

The value of your human capital drops quickly when you retire. You’re essentially abandoning one of your most valuable assets, so it’s not a decision to take lightly. When you stop using it to earn, you stop learning. Your investment in your human capital stops, your skills atrophy, your market connections wither, and your network shrinks. Thus, it’s a bad idea to “try out” full retirement. You may not be able to go back to work once you leave.

Fortunately, full retirement is not the only option! If you like your job, many jobs offer “ease out” opportunities where you can work fewer days or hours or shift to a consulting role. If you would rather do something else, you can repurpose your human capital by moving to a new company, choosing a different and maybe less demanding role, or coaching/teaching the thing you used to do.

Planning is valuable when entering semi-retirement. Ask questions like:

- What will my employer and industry support?

- Where else might I want to go?

- How can I prepare?

If you reduce your income gradually, you’ll have more stability and resilience when you eventually choose full retirement. If you keep working, even part-time, it’s much easier to increase your earnings if you hit a financial setback. Partial retirement also makes financial planning easier because it increases your overall lifetime resources and decreases the amount of full retirement you must fund.

Summary

Human capital is your most valuable asset throughout most of your life. Seemingly small decisions like taking a year off or choosing a different college major can affect its value significantly. Understanding and preserving your human capital helps reduce financial risk later in life.