The GameStop drama had it all – a David vs Goliath storyline, lots of money changing hands, and political involvement. It was very loud, and the numbers were impressive. It happened fast, too – if you blinked, you might have missed the action. It seems important, though – Congress held hearings about it.

But what does it all mean? Should individual investors respond? How?

What happened?

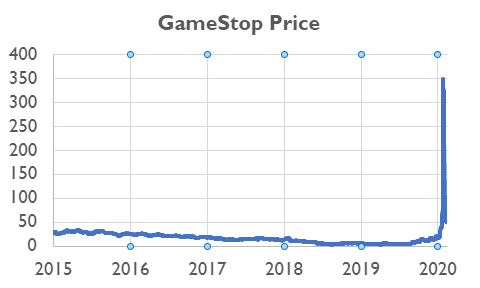

GameStop experienced enormous price volatility between January 12th and February 9th.

After gradually trending down from $28 to $30 per share in early 2016 to $3 to $5 per share in early 2020 (roughly an 80% to 90% decline over 4 years), the stock recovered to $15 to $20 per share by late December of 2020 through early January of 2021 (tripling to quadrupling in 6 months or so).

Between January 12th and February 9th, the stock price exploded to nearly $350 per share (that’s multiplying another 17 (!) times) before falling back to $50 (still 2½ times the early January price).

Why have GameStop stock prices declined so much since 2016?

GameStop sells video game hardware and software through its stores and websites. Its revenue and profitability had suffered due to competition from larger competitors such as Amazon, Best Buy, Walmart, etc.

Why did GameStop’s stock price increase again in late 2020?

Some investors thought GameStop’s competitive prospects had strengthened significantly. They bought the stock, thinking the stock price would increase further if GameStop’s financial results improved.

Why did GameStop’s stock price rise so fast in late January?

1) Some investors (short sellers) disagreed that GameStop’s competitive position had improved. They sold GameStop stock short. That is, they borrowed the stock and sold it. This is profitable if the stock price goes down. Suppose the investor borrows 100 shares of a stock and sells it for $100 a share, then buys it back for $25 to return it. Sale proceeds are $10,000 and repurchase costs are $2,500. The investor’s profit is $10,000 minus $2,500 or $7,500.

Investors who short a stock — borrow it to sell it — must post collateral (usually cash or a letter of credit) with the lender to protect the lender against the possibility that the borrower will not return the stock. Regulations require collateral equal to the value of the borrowed stock. If the stock price rises, the borrower must increase the amount of collateral to match.

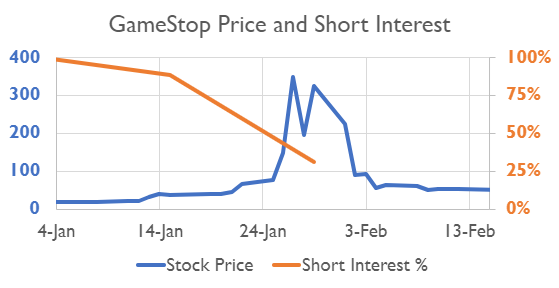

2) Other investors saw that a lot of stock was shorted (in early January, the value of the stock borrowed and sold by short sellers was equal to the entire market value of GameStop!).

Many people communicated with each other through wallstreetbets, an online message board. They discussed the possibility of a “short squeeze” if investors bought the stock. (While there was a lot of discussion about GameStop stock price movements on the message board, there is no way to be certain of the relationship between the discussion and stock market events.)

A “short squeeze” occurs when a shorted stock rises in price. The short sellers must either post more collateral or buy back the borrowed stock to return it. As the stock price rises, each short seller’s position becomes increasingly expensive. In our earlier example, suppose the stock price rises to $225 a share. The short seller must increase collateral from $10,000 to $22,500 or buy back the stock for $22,500 and return it, resulting in a $12,500 loss.

Many investors did buy GameStop stock, and the price rose, a lot! The short squeeze was on.

3) Short sellers either had to post more collateral or buy back the stock at a loss, returning the stock they had borrowed and closing out their short positions. In the graph above, Short Interest (the percentage of shares outstanding sold short) in GameStop stock declined from 89% (!) on January 15th to 31% on January 29th. In buying back the stock, they bid up the price even more, as it reached $350 on January 27th.

Why did Robinhood stop purchases of GameStop stock on its platform?

On the evening of January 27th, Robinhood, a large broker serving individual investors, suspended purchases of GameStop, allowing its customers to maintain or liquidate their holdings, but not to add to them.

Robinhood has revolutionized the brokerage industry by allowing investors to buy and sell stocks without paying a trading commission. Being able to trade at no commissions allows investors to buy and sell stocks freely – reducing “friction” in the markets, making it easier for investor sentiment to influence prices. The GameStop situation is a perfect example of the impact. Information affects prices almost instantly, and prices move very quickly.

In this situation, Robinhood was briefly a victim of its own success. Just as short sellers do, brokers must post collateral to ensure that trades are settled. While a stock trade can be agreed to today, it usually settles on the next business day.

This is analogous to the delay built into a house sale. The Purchase and Sale document binds the buyer and seller to a transaction, but the sale is not complete until settlement, when the buyer’s cash is exchanged for the seller’s deed. Just as the buyer will post a deposit in a house sale, a broker must post collateral as security for a stock purchase.

When its volume of GameStop buy trades grew, Robinhood had to post (a lot) more collateral. It didn’t have enough collateral on January 27th, so it halted GameStop buy trading. GameStop’s price dropped to $193 on January 28th.

By the 29th, Robinhood had raised more money and deposited more collateral. Robinhood buy trading resumed, and GameStop’s stock price went back up to $325.

Why did the stock price drop so fast after January 29th?

While we don’t yet have data on Short Interest for February 15th, it is very likely that most short positions were closed, and the short squeeze was over.

Did Main Street really beat Wall Street?

Yes and no. Some retail (Main Street) investors made a lot of money, and some hedge funds (Wall Street) lost a lot. On the other hand, other retail investors lost a lot, and some hedge funds and mutual funds profited. (Some of these links are behind paywalls).

What does this mean for diversified strategic investors (like me)?

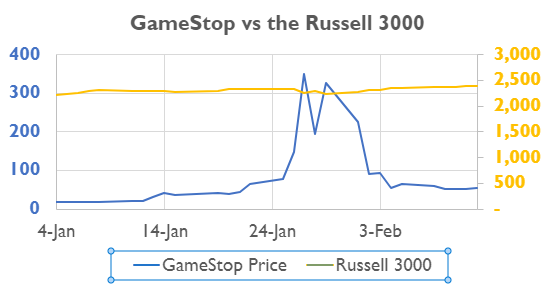

On one hand, you missed an opportunity to make (or lose) a lot of money in a very short, very high stress time. On the other hand, you got to benefit as active investors competed with their dollars to refine the price of GameStop stock.

If you were holding a mutual fund investing in the Russell 3000 index, your portfolio didn’t even notice the GameStop action.

This article originally appeared in Forbes.com.