Recently, I gave a webinar on estate planning, which you can find here. Given the interest in that topic I thought I would translate some of that content into a short article.

I will attempt to explain estate planning from a bird’s eye view. Estate planning is complex, riddled with esoteric vocabulary and counterintuitive rules that vary from state to state. It cannot be distilled into a few hundred words. Nevertheless, a summary overview can provide a useful introduction.

Why am I writing this article and why should you read it?

- Everyone needs an estate plan

- Many people put off creating an estate plan

- We offer an experienced perspective on estate planning

It’s important to say this at the outset: while I am trained as an attorney, I am not a practicing attorney. I’m approaching this topic from a financial planner’s perspective. Nothing in this article should be taken as legal or tax advice. Estate planning is very situationally specific. You should strongly consider hiring a trained professional to help you.

What is an estate plan?

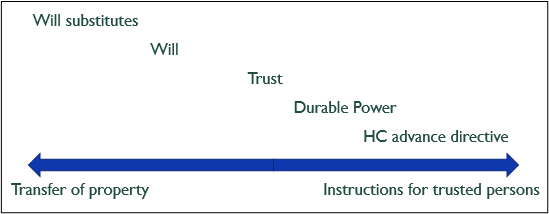

An estate plan is a set of documents that spells out how you want to transfer property after death and provides instructions on how to manage your affairs if you die or become incapacitated. I find it helpful to think about the elements of an estate plan on a spectrum. On one end, there are tools that deal primarily with the transfer of property upon death. On the other, there are instructions for trusted persons. Some of these items can change positions, moving closer to either end (this is particularly true with trusts, which are very flexible). I find the graphic below useful when thinking about estate planning tools at a high level.

Not every estate plan includes all these elements, but it will include most. Below I define each element and describe how it fits into an estate plan. But before that, I first need to define what we mean by ‘estate’.

What is an Estate?

When a person dies, the property they leave behind is known as their estate. Much of estate planning deals with how to transfer property from a person’s estate to survivors. Transfers occur in one of two ways. Probate refers to the court-supervised process that determines the validity of a will and oversees its execution. The probate estate is all property that passes through the probate process. While this can be a bit complicated, generally speaking, the probate estate consists of all property owned in an individual’s name when they die. Think about a bank account or a house owned individually. Upon death, property of this type flows through the probate process.

Alternatively, property can pass outside of probate. The non-probate estate consists of all property transfers that avoid probate. For example, if someone owns a bank account in joint tenancy, upon death their interest would pass automatically to the surviving owner. Certain types of trusts can also be used to transfer property to beneficiaries outside of the probate process.

Whether it is preferable to transfer property through or outside of probate depends on many factors. An estate planning attorney can help you determine what is best for your situation.

The Elements of an Estate Plan

Will substitutes

A will substitute is any instrument that transfers property upon an owner’s death outside of the probate process. There are two broad categories of will substitutes:

- Title – refers to the legal right to ownership of a property. Certain types of title bypass probate automatically, such as joint tenancy and some trusts.

- Contracts – are agreements to transfer an interest in an asset to one or several beneficiaries. These types of agreements are limited to special types of property, such as life insurance and retirement accounts. Upon death, the named beneficiary automatically receives the property.

Will substitutes have many potential benefits. They are efficient means of transferring property. Transfers are generally private affairs. By contrast, probate documents become public record after an estate is settled. Also, certain assets, like IRAs, provide tax deferral benefits when they are transferred directly to beneficiaries (rather than to a trust).

Will substitutes also have a few drawbacks.

- Unlike a will, there is no “one place” to update your estate plan. If you have multiple retirement accounts, you will have to update the beneficiaries on each account if your estate plan changes.

- Outright transfers via joint tenancy or retirement beneficiaries do not allow much flexibility. Naming a child as a beneficiary on an IRA may be an efficient way to transfer assets, but it may not always be prudent for a young or financially irresponsible child to inherit a large sum.

- If the instructions in a will conflict with those of a beneficiary designation or pay on death instructions, it can invite litigation.

Wills

A will is a legal instrument that specifies how a person wants to manage their probate estate after death. It is a core estate planning document. Nearly every estate plan, even those designed to avoid or minimize probate, includes a will.

Wills can do many things. They can:

- Distribute property to designated persons or organizations

- Designate a guardian for minor children

- Identify an executor or personal representative – the person who will be responsible for managing the probate process

- Create or funnel assets into a trust

A will-based estate plan is sufficient for many people. In cases where more flexibility is needed, attorneys will sometimes recommend trusts.

Trusts

There are many different types of trusts. ‘Totten trusts’, also known as ‘pay on death accounts’, are just a type of will substitute that transfers property upon an owner’s death. Irrevocable trusts file their own tax returns and can exist for many generations. Since I cannot cover all the types of trusts that are used in estate plans, I must cover this topic at a very high level.

A trust is a legal relationship in which a trustee holds property for some else’s benefit. Trusts involve three parties. A grantor, who creates the trust. A trustee, who holds and manages the property. And a beneficiary, who receives the benefits of the trust. All three can be the same individual.

So why do people use trusts in estate plans? Trusts can do many of the same things wills do, plus they can provide:

- Privacy – Trusts can avoid probate and are more private than wills.

- Predictability – Trusts are more difficult to contest than wills.

- Taxes – Trusts can be used to reduce or even eliminate estate taxes.

- Care while alive and well – With trusts, you can designate someone else to manage the property for your or someone else’s benefit. This can occur upon establishing the trust or upon some future event, like a serious illness or incapacity.

- Flexibility – With trusts you can manage how beneficiaries can access the property in the trust. For example, sometimes beneficiaries are entitled only to income. Or beneficiaries can access the principal for certain types of expenses, like healthcare or education, but not others, like a Lamborghini.

- Gifts to charity – Trusts can be structured to provide benefits to a charity immediately or in the future. or even after death.

Trusts can be extremely useful estate planning tools, but they come at a cost. An estate plan that uses trusts will be more costly than a wills-based estate plan. Whether trusts make sense for you and your family depends on your preferences and needs.

Durable powers of attorney

Moving further along the spectrum from property transfers toward managing affairs is the durable power of attorney (in some states called the financial power). This document is used to designate someone to manage your financial affairs if you are unable to do so. A durable power of attorney is a legal agreement where a ‘principal’ (the person delegating power) names an ‘agent’ to act on their behalf. The ‘durable’ part of the arrangement means that it stays in effect if the principal becomes incapacitated, by an accident or illness, for example.

There are other ways to delegate responsibility for your financial affairs. If you are married, your spouse will be able to make financial decisions for any joint property you own. But it’s important to think about what would happen if you are the surviving spouse or if your spouse may not be up to the task of managing the household affairs by themselves. If you put assets into a trust, you can delegate a co-trustee or successor trustee to manage assets held in your trust for your benefit. Importantly, a trustee cannot access or manage assets not in the trust, such as IRA assets. For this reason, even trust-based estate plans should include a durable power of attorney.

Healthcare advance directives

Finally, there is the question of future medical decision-making. If you could not give your consent, what type of care would you want and under what circumstances? Who would you choose to make the difficult decisions if you were unable? A healthcare advance directive can answer both questions. Although the details vary by state, the advance directive is composed of two documents. A living will (not the same thing as a will) leaves instructions for what type of medical treatments you would elect under different circumstances. A healthcare power of attorney names an agent to make healthcare choices for you in the event of incapacity.

In Summary

I hope I’ve been able to demystify estate planning somewhat in this article. Estate planning deals with more than just transfers of property, although that’s very important. It can also help you choose people to make financial and medical decisions in your best interest if you become unable to do so. It’s essential that all the pieces work together so that your plan works as intended.

I hope to write and present more about estate planning in the future. If you find this article helpful, please let me know. If you have estate planning questions, I would appreciate hearing from you.

To contact me, please email me at fnapolitano@sensiblefinancial.com.