In my last article I summarized the trailing 15 years of active management versus passive management performance data (spoiler alert: passive won). Looking solely at fund returns over that timeframe, we saw that the overwhelming majority of active managers trailed the performance of their relevant benchmarks.

But returns are only part of the analysis. Risk matters as well. For example, a lower-return investment may be preferable to a higher-return investment if it is sufficiently less risky. This is why an investor concerned with principal protection would choose a Treasury bond over a high-yield, or “junk”, bond. Sure, the junk bond may earn more, but it could also lose money. The Treasury bond most likely will earn less, but you won’t lose money.

In this article I’ll introduce the concept of risk and what it means for an investor to be risk-averse. I’ll then show that active management, on average, leads to the opposite of what a rational investor should prefer in an investment.

What is Risk?

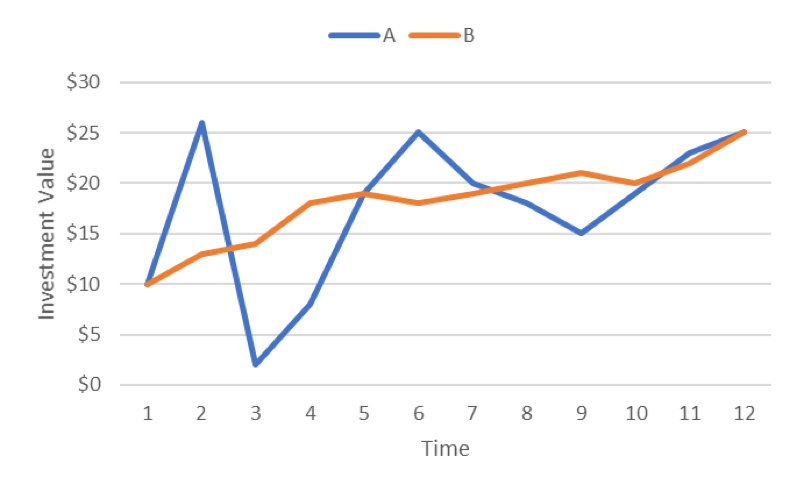

Imagine you are evaluating two mutual funds, A and B. Both funds invest in the same group of US large stocks and so each fund has the same expected return, i.e. the return an investor expects based on anticipated rates of return.

You plot the twelve-month history of the two funds on Morningstar.com and find out that over that timeframe both funds returned the same amount.

Both funds invest in the same basket of stocks. Both funds yielded the same return last year and have the same expected return for next year. How do you choose which one to buy?

All things equal, a rational investor would choose fund B (the orange line). Its expected return is the same as A’s, but at a lower risk. You may know this intuitively by looking at the chart, but we can measure this risk using statistics. Standard deviation is a statistical measure of the degree to which members of a set differ from their mean (the higher the standard deviation, the higher the risk). Fund A’s standard deviation is 7.5%, where B’s is only 4.0%. Based on these factors, B is probably the better investment.

This brings us to an important point:

Given the same expected return, a rational investor will choose the investment with the lower level of risk.

The logic behind this statement is straightforward. Why would you choose a riskier investment if a safer one exists offering the same expected return? (At the extreme, imagine a risky investment and a risk-free investment with the same expected returns.) To take on higher risk, investors expect to be compensated in the form of higher (expected) returns. This is known as the risk-return tradeoff.

So if two investments have the same expected return but different risks, why would anyone ever buy the riskier investment? The only reason would be that they like risk. This type of investor we call risk seeking. By contrast, a risk averse investor prefers to avoid unnecessary risk. It’s not that this person is unwilling to take any risk, but rather that a risk averse investor is someone who, when faced with two investments with similar returns, will prefer the investment with the lower risk.

Is Active Management Uncompensated Risk?

Taking what we know about investment risk, can we compare the risk of active management to that of passive investments like index funds? Unlike the above example (whether to invest in A or B), you cannot buy active management. In other words, you can’t buy the average active fund. (Note however that you can buy an index fund). Rather, you must choose between a specific actively-managed fund and some alternative passive fund.

We can approximate the risk of active management by ordering a sample of actively managed funds by their annual returns over a sufficiently lengthy time. If the funds’ returns cluster close to the index’s, this would imply lower risk than if the returns are widely spread (the idea is similar to but not the same as standard deviation). Said another way, if all funds perform similarly to the index, active risk (the extra risk of an actively managed fund relative to its passive benchmark) is low. On the other hand, if funds perform less predictably then active risk is high and investors should expect to be compensated in the form of higher returns.

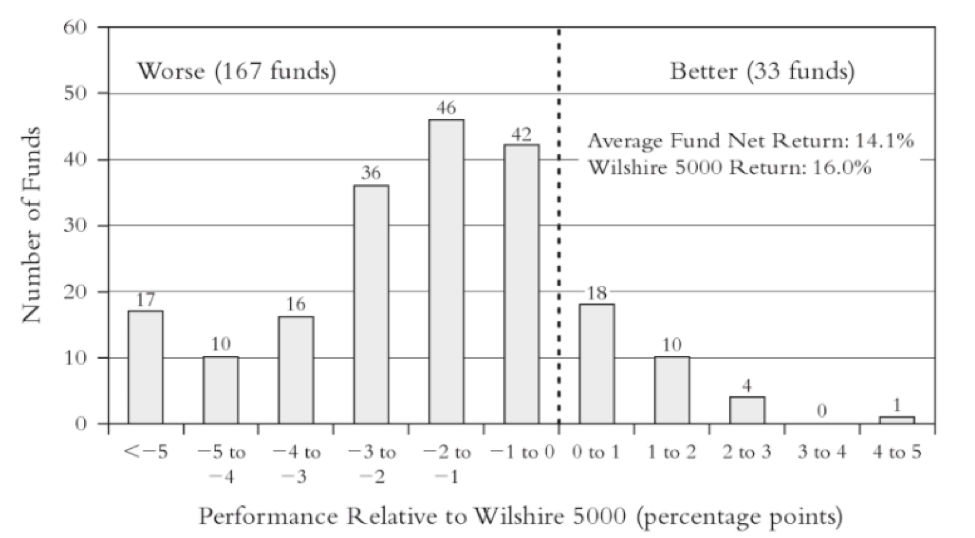

Sensible Financial has used a version of the below graph for the past fifteen years. It was originally published in John Bogle’s Common Sense on Mutual Funds. It compares the annualized performance of 200 growth and value funds over a 15-year period ending on June 30, 1998 to that of the Wilshire 5000 Index (a broad-based US stock index). The index returned 16.0% annualized over that time while the average active mutual fund returned 14.1%, with 33 funds beating and 167 funds losing to the benchmark.

From Bogle, Common Sense on Mutual Funds, Updated 10th Anniversary Edition. Copyright © 2010 by John Wiley & Sons, Inc. Reprinted by permission of John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

This data supports the conclusion that on average actively managed funds underperform the index (but we already knew that). The more interesting story is what the graph tells us about active risk. Even a cursory glance shows us that the variation of returns around the index is significant. Sure, you could have been among the lucky losers who “only” lost between 0% and 1% (annualized) to the index. However, it’s more likely that you would have lost 1% to 2% to the index every year. In fact, you are about just as likely to have lost more than 5% per year, every year for 15 years in a row, than to have beaten the index by between 0% and 1%!

That’s a lot of unpredictability. And, you probably don’t like unpredictability (remember, you’re risk averse). In fact, as an investor you should expect to be compensated by taking higher risk in the form of higher (expected) returns. With active management, you get the opposite! Which leads me to another important point:

Investors prefer high return, low risk investments. With active management, you get lower return at higher risk.

NOTE: Had you chosen the one fund that returned 4% to 5% per year every year above the index, the above statement would make you laugh so hard you’d fall out of your chair and spill your margarita all over yourself on some island paradise. But unless you know how to consistently pick a winner (and there’s scant evidence that people do), understand that when you choose active management over passive, on average you’re choosing a higher risk, lower return investment. And we just don’t think that’s sensible.

So what’s a rational investor to do?

We continue to believe that the sensible approach to investing in the market is to choose low-cost, passive funds such as index funds. Not only do they yield higher returns than active funds, they do so at lower risk.

Frank Napolitano is a Senior Financial Advisor and CERTIFIED FINANCIAL PLANNERTM. To speak with Frank or another member of our team about your financial future, get in touch today.