Axel Börsch-Supan, a German expert on public pensions, spoke at the 18th Annual Meeting of the Retirement Research Consortium in Washington, DC earlier this month. He offered an implicit framework for how public pension systems should work. He suggested that these systems should:

Axel Börsch-Supan, a German expert on public pensions, spoke at the 18th Annual Meeting of the Retirement Research Consortium in Washington, DC earlier this month. He offered an implicit framework for how public pension systems should work. He suggested that these systems should:

- Be operationally transparent

- Automatically adjust to changes in the supporting economy

- Not attempt to be the sole pension for every citizen

- Nevertheless, provide a basic benefit that keeps senior citizens out of poverty

He drew comparisons between the European systems and the situations in the various European countries, and the system and situation we have here. In brief, the US enjoys fortunate demographics relative to its European counterparts, but our system could likely improve substantially if we adopted some of the more innovative European approaches.

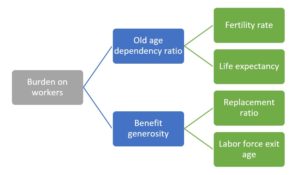

Our public pension system, Social Security, is a “Pay as You Go” (PAYGO) system. That is, workers’ tax payments fund distributions to retirees.[1] In a PAYGO system, the burden on workers depends on:

- How many retirees each worker must support (the dependency ratio), which in turn depends on

- The fertility rate, or how many children each woman has; and

- Life expectancy

- The generosity of retiree benefits

Intuitively, the more retirees there are for each active worker, the more each worker must pay in taxes to provide benefits for all of the retirees he or she effectively supports.

Fortunate demographics for the US

Major demographic factors in assessing a public pension system:

- The old-age dependency ratio – the number of retirees per person of working age. This measure quantifies the burden that each worker bears in supporting retirees.

- It is much higher in some countries (Japan, Italy, Germany, Spain) than in the US [Japan is not in Europe, but Börsch-Supan sporadically included information on Japan.]

- The US dependency ratio will increase from just over .2 (1 retiree for every 5 workers) now to almost .4 (1 retiree for every 2.5 workers) by 2050, which will increase the strain on our system.

- Other systems will be even more stressed, most notably Japan whose ratio will increase from nearly .4 now to over .8 (getting very close to 1 retiree per worker!) by 2050.

- Unfortunately, saying other systems are even worse off than Social Security is unlikely to make US workers of 2050 feel any better!

- The dependency ratio will change in part depending upon

- The total fertility rate (children born per woman) which is much higher in the US (just over 2) than in Germany, Greece, Italy and Spain (all under 1.5). Higher is better – more children now means more potential workers soon – another US advantage.

- Life expectancy (which has been steadily increasing in all developed countries) – from the public pension stress perspective, lower is better – shorter life spans mean fewer retirees per worker. Unfortunately, the US has something of an advantage here, albeit a small one.

US offers less generous benefits

When we are retired, we want more generous benefits. Economists measure benefit generosity on two dimensions:

- Gross replacement rate – benefits after retirement as a percentage of earnings while working. High rates mean more generous benefits – a rate of 100 would mean that retirement benefits equal pre-retirement earnings.

- On this dimension, Greece is highest at 110 (retirement benefits greater than earnings!), Germany is middling at 58.

- The US is relatively low at 50.

- Labor force exit age – the average age of retirement. Earlier ages mean more generous retirement benefits because retirees get benefits for longer.

- France is early at 59, Germany and Greece are middling at 62.

- The US is late at 65.

- US Social Security does not do as well as many European systems (including the UK) at preventing old age poverty.

- In many European countries, including Germany and the United Kingdom, 10% or less of the over-65 population have income less than half the national median income.

- The US, Greece, Spain and Ireland all have more than 20% of the over-65 population with income less than half the national median.

Characteristics of a successful and sustainable system

Börsch-Supan concluded his remarks by reviewing the attributes of a public pension system that will work in the long run. Some of these attributes are not purely economic – public pensions are, well, public, and public means political. Based on both his economic analysis and his political experience, Börsch-Supan believes that the best public pension systems will exhibit

- Fairness – annual benefits will be aligned with lifetime contributions, retirement ages will adjust automatically as life expectancy changes

- Transparency about redistribution – any benefits arising without contribution can be attributed to child-raising, unemployment, military service, etc.

- Automatic responses to macro-economic conditions to keep the system solvent. For example, annual benefits

- Decrease as longevity increases

- Decrease as fertility decreases

- Increase as economic conditions improve

Believe it or not, Germany actually embedded a sustainability equation in its most recent public pension law, according to Börsch-Supan. If done well, Social Security reform might actually never need to be done again!

[1] Strictly speaking, when workers’ tax payments exceed benefit payments to retirees, as they do now, the Social Security system lends the surplus to the broader government, which issues special bonds to the Social Security system in return. As a practical matter, however, when benefit payments come to exceed workers’ tax payments, as they are currently forecast to do by 2033, the broader government will have to cut other programs or raise other taxes in order to pay off the bonds. The Congress may be unwilling to support either of these actions.