In the fourth article in my series on investment returns from 2000-2019, I’ll cover international bonds. The first three dealt with US stocks and bonds, international and emerging markets, and factor investing.

This article originally appeared in Forbes.com.

Investing in international bonds may help diversify your portfolio. Even if you don’t expect higher returns, you could enjoy a decrease in risk over the long term by including them in your portfolio. That’s because foreign bond returns change differently than US bond returns do – sometimes when US bond returns are poor, international bond returns will be good, and vice versa.

On average, we don’t expect foreign government and investment grade corporate bonds to return more than comparable US bonds because their risks are similar, and returns should be proportional to risk.

What are the major bond risks?

- Credit risk: The issuer might not pay interest or return principal.

- Interest rate risk: Interest rates might change, reducing the value of a bond’s coupon and principal cash flows.

The international bonds we are considering here (captured in the Bloomberg Barclays Global Aggregate ex-US Bond Index (hedged to US Dollar)) are issued by governments and corporations in the EU, Japan, and Australia. Bond markets in these countries are similar to US bond markets.

Non-US bonds frequently pose an extra risk. They represent obligations in non-US denominations. When these currencies fluctuate in value relative to the dollar, foreign bond values fluctuate, too. Currency fluctuations represent an additional, “non-bond,” source of risk.

Purchasing “hedged” international bonds improves your chances of risk reduction. Hedging translates foreign bond cash flows from their native currencies into dollars, dramatically reducing currency risk.

That’s the theory. How did it work in the first two decades of this century?

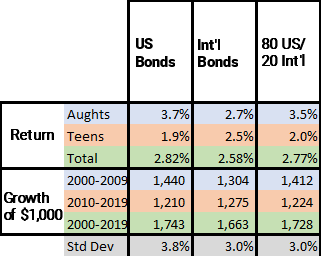

In the aughts, US bonds returned 1% per year more than hedged international bonds, adding about $135 more for each $1,000 invested and held for the full 10 years. In the teens, fortunes reversed, and international bonds led, adding an extra $65 for each $1,000 invested. For the full period, US bonds won out, but the difference was small ($80 per $1,000 over 20 years).

However, international bonds play a different portfolio role than value or small stocks. They are primarily a diversifier. We don’t expect them to outperform US bonds (although we wouldn’t be disappointed if they did).

Diversification is primarily about reducing risk. The rightmost column illustrates a diversified portfolio of 80% US and 20% international bonds. In the aughts, the mix underperformed US bonds slightly. In the teens, the mix outperformed US bonds slightly. For the entire period, the mix roughly matched the US-only portfolio in performance, trailing by only .05% per year, or 5 basis points. The risk of the mixed portfolio was lower (standard deviation 3.5% vs. 3.8%).

Was the risk reduction worth the slightly lower return?

We can use the Sharpe Ratio to assess how the return of an investment relates to its risk. The Sharpe Ratio divides an investment’s excess return (extra return over the risk-free rate) by its extra risk or standard deviation. A higher Sharpe Ratio indicates a more attractive investment. Over the two decades, the Sharpe Ratio for the globally diversified bond portfolio was .93 versus .88 for the US-only portfolio. Diversification paid off.

In fact, even in the aughts, when US bonds enjoyed a 1% annual return advantage, including hedged international bonds in the portfolio produced a slightly higher Sharpe Ratio, .81 vs .79 (not shown in the table). You might have thought of diversification as an advantage in stock investing, but it can help with bonds, too!