“Over the past century, we’ve created the greatest gift in the history of humanity — thirty extra years of life — and we don’t know what to do with it! . . . What we need is not to put off death a little longer but to write a new narrative of aging as it could be.”

– Joseph Coughlin, Director MIT Age Lab

Why is it so hard to write a new narrative about the next 30 years? For many of us, the stereotype about the retirement transition gets in the way.

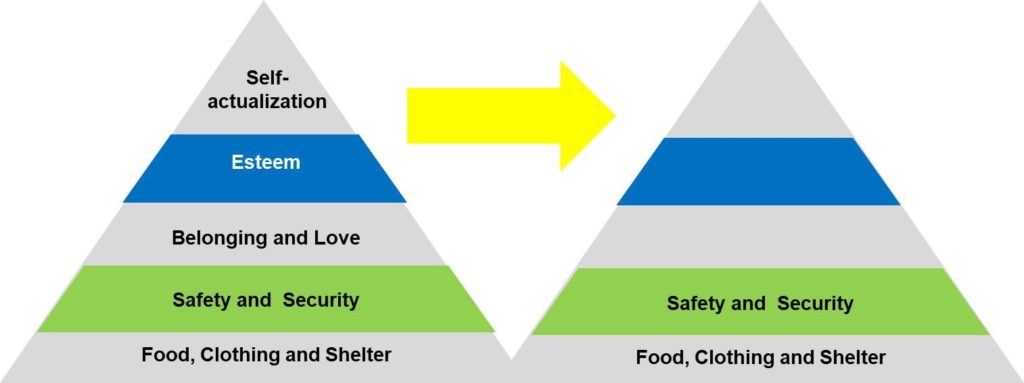

Maslow’s hierarchy of human needs provides a useful model to understand the challenge. This hierarchy is often seen as a pyramid with basic needs, food clothing and shelter at the base; extending upward to safety, love and belonging, esteem and self-actualization on the top.

For many of us, work fulfills many if not most of the lower levels in the pyramid. For example: it provides the money to satisfy our physiological and safety needs and for some, it provides a sense of connection, status, and recognition associated with esteem. For a few, work may fulfill the “desire to be the most that one can be,” what Maslow defines as “self-actualization.”

With paid or volunteer work…………………….Without work

However when one leaves work, all the needs that it satisfied are still there, but their fulfillment is gone. As one client said, “In addition to pay, my work structures my day. I get interesting problems to solve, many of my social needs are addressed by the people I work with and I get recognition and status from solving the problems at work. What am I going to do without this?”

The key is to answer the question, “What is the meaning and purpose of my life?” The Japanese have a saying, “To live to 100, follow your ikigai, your reason for being. Having ikigai would induce you to lead a healthier lifestyle, with more exercise, increased social activities, and life-long learning.”

People who answer the meaning question live longer. According to two studies, those who could articulate the meaning and purpose of their lives lived longer than those who saw their lives as aimless. It didn’t seem to matter what meaning participants ascribed to their life, whether it was personal (like happiness), creative (like making art) or altruistic (like making the world a better place). It was having an answer to the question that mattered.

But why is creating a new narrative so difficult at the time of retirement?

More than just stopping work, retirement is a commencement of the next stage in one’s life, a time for writing a new narrative about oneself.

One part of why this is so difficult is due to the way our brains make meaning from what we experience. We need meaning to thrive, even to survive. While working, we train our brains to ignore most things, while we focus on work and family. However when we retire, we must retrain our brains to see new patterns and make meaning in new ways. We have to revisit our lives and see the world in new ways. Here are two examples of what can happen:

Pat was the main breadwinner in her family. She was concerned that her husband was nearing retirement. He was being celebrated by his co-workers. Her husband had a plan for what he would do next. She didn’t.

By using several thought-provoking exercises she was able to break free from the boundaries of what had always been, and to imagine and plan for what might yet come to be. These resulted in a plan that she is enthusiastically implementing — a plan that is specifically tailored to her personal needs and dreams.

Chris was an engineer facing retirement. His vision of retirement was a black hole, an endless abyss.

However, by using several exercises based on Design Thinking, a non-linear, iterative process which seeks to understand users, challenge assumptions, redefine problems, and create innovative solutions, he was able to revisit his life with a new filter. These exercises helped him think through his next priorities and actions as he transitioned into retirement. He loved sailing, especially ocean voyages. He has always wanted to sail single-handed across the Atlantic. To do this, he would have to develop new skills in meteorology, add new equipment to his sailboat, and practice by taking several shorter solo voyages.

He contacted experts in each of these areas. They were glad to work with him to learn the new skills, point out the additional equipment needed for his boat, and identify the trial runs that he would need to practice. At the end of our work together, he had a network of contacts and a 2-3 year plan culminating in a solo sail across the Atlantic.

The hard part for many of us is that we see this transition as just an ending. However, we can find that once we begin, the next phase of our journey unfolds before us.

Tom Sadtler, president of Design What’s Next, is a coach with over 35 years of experience as a business executive and in psychiatric social work. His approach to coaching is distinguished by a deep compassion for people and an understanding of how leaders succeed. His life, business, and social work experience enable him to guide other executives through transition processes that result in more energy, engagement, and meaning in their lives. Tom has a B.S., in psychology from Tufts University, an M.S.W. from Boston College, and an M.B.A. from Harvard Business School.