Congress recently passed a “stopgap spending bill” to fund the U.S. government for 45 days beginning Oct. 1. This bill stopped the federal government from shutting down, at least temporarily. It follows the suspension of the U.S. federal debt ceiling through the end of 2024 that passed in early June 2023.

Press discussions focused on political polarization and the practical implications of a binding debt ceiling or government shutdown. We’ve heard a lot about what might make the government delay Social Security checks or close national parks.

These “crises” are symptoms of fiscal realities and policy disagreements that the media largely ignores. The projected growth of federal government debt is unprecedented. The political parties seem to be unable to agree on policies, but they share an unwillingness to ask Americans to pay for their government services and social insurance programs.

Some context: U.S. federal debt through history

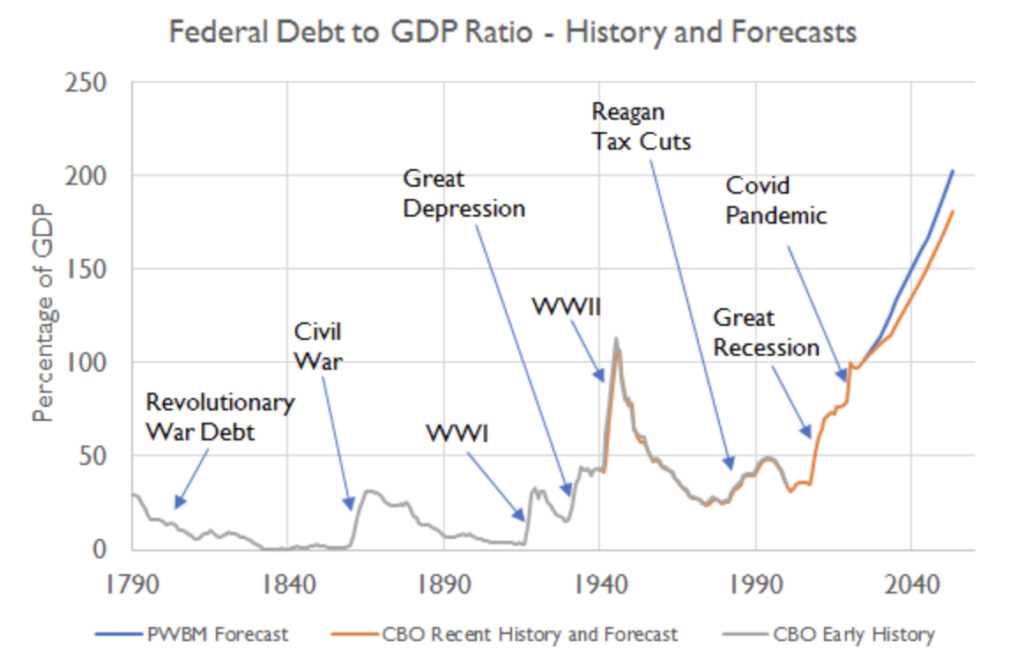

For most of American history, debt increases were responses to major crises. After each crisis passed, the government paid down its debt. The first exception to this pattern was during the 1980s, when Reagan cut taxes, but not spending. Unlike in the past, there was no crisis behind the debt expansion. The government didn’t finish paying down its World War II debt, an unprecedented action.

The government reduced its debt somewhat during the Clinton administration. When the Great Recession struck in 2007-2009, it made no effort to pay down the debt afterward. The COVID-19 pandemic followed in 2020. Again, the government seemed uninterested in reducing its debt.

The U.S. Congressional Budget Office (CBO) and independent forecasters expect U.S. debt to grow as a percentage of gross domestic product (GDP) for the next 30 years.

Looking at debt as a percentage of GDP supports comparisons with countries of different sizes and roughly assesses countries’ ability to repay their debts. The forecasters’ projections suggest that the U.S. debt-to-GDP ratio will reach levels never seen before. Only during World War II did the ratio even get close to the current level.

Historical trends suggest that the debt-to-GDP ratio should be declining. We are not at war, nor do we face an extraordinary economic or health crisis. Neither the Great Financial Crisis nor the COVID-19 pandemic came close to the severity of World War II, during which 12 million Americans (out of a population of 140 million) served in the armed forces, and 405 thousand died. Our debt is spiraling out of control.

Why is U.S. federal debt so high?

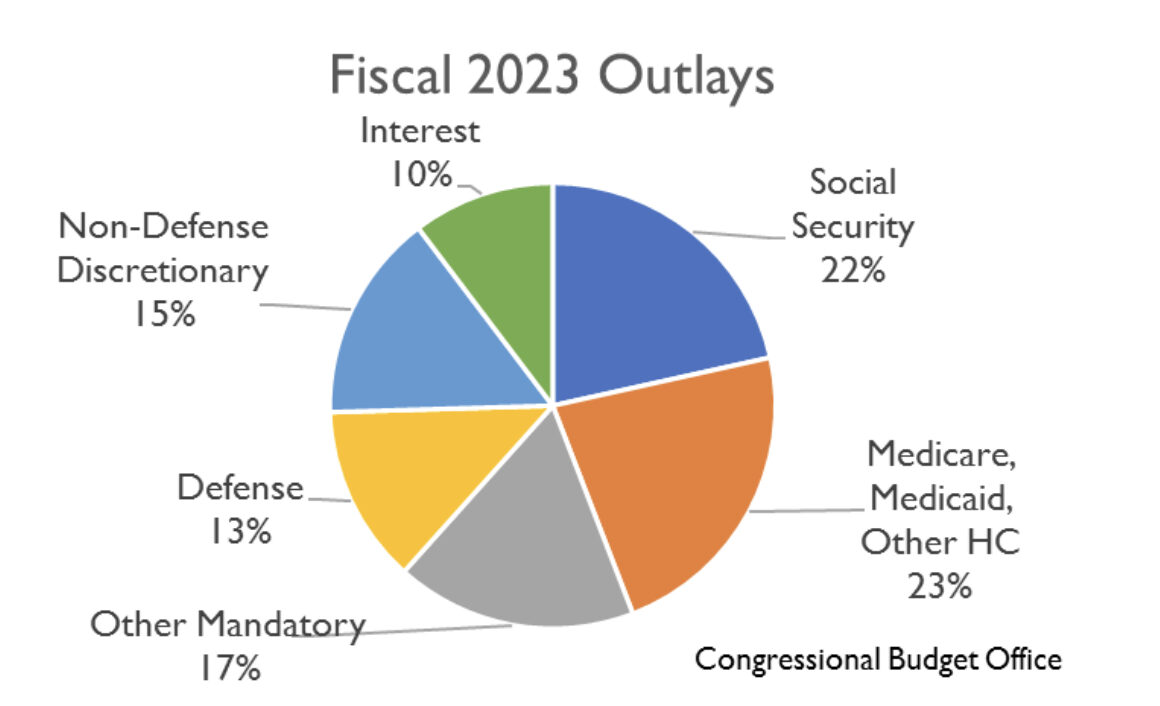

Forecasters don’t focus on military or infrastructure spending because the government spends relatively little money there. Much of the government’s spending (62 percent!) is on social insurance items like Social Security, Medicare and Medicaid. The interest cost of financing the government’s debt also contributes to the debt.

Social Security

For its financial plans, Sensible Financial assumes Social Security benefits will decline and FICA taxes will increase in the early 2030s when the Social Security Trust Fund runs out. The Social Security Trustees have been warning for some time that the program faces effective insolvency.

The CBO projects the proportion of the population eligible for Social Security benefits to rise from 20 percent to 25 percent by 2053. More people will be receiving Social Security benefits. At the same time, fewer workers will be paying Social Security taxes.

Benefit payments have exceeded tax receipts for some time. The Social Security Trust Fund has been making up the difference. The gap will keep getting worse unless taxes increase, benefits decline, or both. Benefits will continue, but they may be smaller than promised.

Medicare

Medicare’s finances are facing similar factors. Over time, a larger percentage of people will be eligible for Medicare. An aging population requires more healthcare, so the cost of care per person will likely increase. Medicare financing shares another similarity with Social Security – a trust fund. The Hospital Insurance (HI) trust fund pays for Medicare Part A benefits. Projections indicate that the HI fund will run out by 2035.

Interest

If large federal deficits continue, the debt will grow. Deficits are the amount the government spends over the funds it receives from taxes. Federal debt is the cumulative history of deficits. Interest costs on federal debt will rise because the debt itself is getting bigger. The effect will be even larger if interest rates remain high.

Combined impact

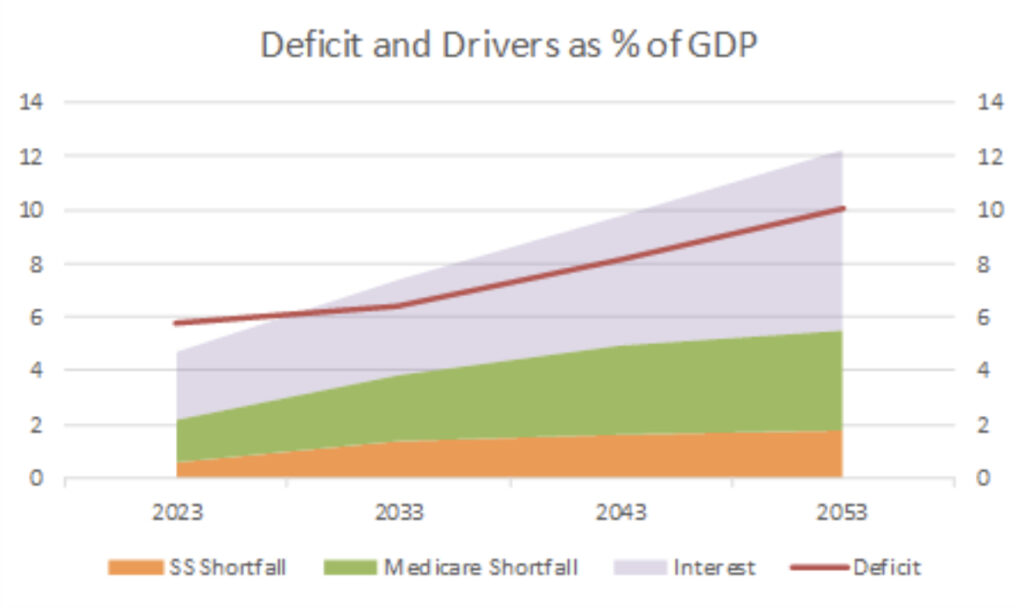

The chart illustrates the effects of the Social Security shortfall, Medicare shortfall and interest on the deficit. This year those three factors account for most of the deficit. By 2053, they will account for 12 percent of the GDP, a bit more than the projected deficit of 10 percent. A variety of small factors make up the difference.

Why do the deficit and federal debt matter?

Growing government debt at this scale prompts two concerns.

First, debt reduces the government’s flexibility to respond to a crisis. Adding still more debt, especially in a crisis, may make investors uncomfortable. This could result in higher interest rates. Higher inflation is possible too, if investors worry that the government will print money to make principal and interest payments.

Second, high levels of government debt can crowd out private investment. Investable funds are finite. If more funds go toward financing government debt, fewer are available for private investment. If interest rates rise, private companies will borrow less and invest less. This slows economic growth and growth in personal income.

Why is government debt growing so much?

Demographic trends are the main contributor. People are having fewer children than they used to. The existing population is continuing to age. Thus, the proportion of older adults is increasing.

Twenty percent of the population is older than 65 now. By 2053, 25 percent will be over 65. Citizens in this age group are the primary recipients of Social Security and Medicare benefits. They provide a built-in constituency that jealously guards their entitlements. We need only look at the ages of many national political leaders (Biden, Trump, Schumer, Pelosi, McConnell, etc.) to see the power of this age group.

Is debt growth through 2053 inevitable?

Current projections of government debt assume Social Security and Medicare funding will stay the same. However, when these social insurance trust funds run out, there will likely be a political reckoning. These insolvencies are likely to occur in the early- to mid-2030s. The government will need to change where Social Security and Medicare get their funding. If they don’t raise taxes, they’ll have to shrink benefits or take funds from the United States’ general revenues.

Most voters over 65 will oppose benefits declines. Congress would have to approve drawing funding from general revenues. This would make the underfunding of Social Security and Medicare, which the trust fund structure currently obscures, much more obvious.

Younger generations fund Medicare and Social Security benefits in two ways. First, they pay most of the taxes that fund these programs. Second, they will be responsible for the debt incurred to make up the difference between benefits and dedicated taxes. They will be more likely to oppose both higher taxes and maintaining benefits at current levels.

By the 2030s, there will be a new generation of political leaders. The problems of these major benefit programs will be the subject of intense political debate. No one can predict the outcome. Competing solutions have not yet emerged in political conversation.

What should investors do to protect themselves from the consequences of government debt?

The Federal Reserve recently increased the interest rates it controls in response to high inflation. It’s unlikely that interest rates will return to their very low pre-Covid levels soon. High interest rates are good for lenders, and most investors are lenders/bondholders. High government debt also makes inflation increases more likely during crises that require government spending. A financial crisis, epidemic or disaster could push inflation even higher.

There are a few things you can do to protect your finances during this high-interest, high-debt time.

- Hold TIPS bonds. Investors can protect themselves from inflation surprises by holding inflation-protected bonds (TIPS). Sensible Financial recently expanded the proportion of TIPS in its customers’ bond portfolios. We plan to continue this strategy indefinitely.

- Hold international securities. Holding non-U.S. securities as part of a diversified portfolio protects against domestic financial difficulties. Investors often overlook this benefit of international investment exposure.

- Contact your representatives. The political parties differ in their preferred policies, but the debt has increased on each party’s watch in the last few decades. Neither party has proposed a coherent approach to managing or reducing the federal debt. We can let our elected representatives know we’re worried about the debt and want them to find a solution.

For help protecting your financial interests against federal debt, reach out to a Sensible Financial advisor.

Photo credit: Douglas Rissing