Risk-free Banking Is An Illusion

Everybody wants a sure thing.

While most people want a chance at excellent investment returns, very few are happy with the trade-off – the risk of loss.

We don’t want to lose. In Thinking Fast and Slow, Nobel laureate Daniel Kahneman explains that people are twice as unhappy with a loss as they are happy about a gain of the same size.

Our politicians and institutions promise to deliver security and protect us from loss because we want them to.

Banks, deposits, loans, and risk

Banks (with Silicon Valley Bank (SVB) as a poster child) are an excellent example of the difficulties and unintended consequences that follow from attempting to eliminate risk. I wrote about this in an earlier article for Forbes.

We’ll start with a summary balance sheet for SVB, one of the banks that recently became insolvent (went broke).

SVB’s $173 billion in deposits were liabilities, amounts that SVB owed. SVB borrowed these deposits (from its depositors), promising to pay them back on demand (whenever the depositors asked for them). The other liabilities ($22.4 billion) were mostly short- and long-term debt, money that SVB owed to lenders who were not depositors.

SVB’s assets, what SVB owned, included $13.8 billion in cash, $120 billion in securities (mostly US Treasury bonds and mortgage-backed securities) and $73.6 billion in loans (SVB’s loan customers included many startup companies).

The right (liabilities and equity) side of the balance sheet also included $16.3 billion of shareholders’ equity. Shareholders’ equity is the difference between assets and liabilities.

The balance sheet illustrates how banks work. When a bank is founded, the original shareholders contribute money to provide starting capital. Bank managers borrow money from depositors and lend it to companies and other borrowers, hoping to make a profit by charging higher interest rates on their loans than they pay on their borrowings, including deposits.

If the bank makes a profit, shareholders’ equity increases. If the bank loses money, so do the shareholders, as shareholders’ equity declines. If the bank loses too much money, the deposits and other liabilities that the bank owes will be larger than the bank’s assets. The bank won’t be able to pay back what it owes. Shareholders will lose their entire investment. Depositors might lose money.

Said slightly differently, shareholders’ equity absorbs the bank’s loan losses until it is exhausted. Beyond that point, depositors’ funds are at risk.

Two fundamental sources of instability:

Depositors and bankers have very different beliefs about how banks work. Depositors’ beliefs are at best inaccurate.

Depositors think that their money is safe – maybe in a safe-deposit box that magically pays interest. The very language (“deposit”) conflicts with the reality. Two definitions from Oxford Languages via Google make the point (I have added emphasis in bold italics):

- Deposit (noun): a sum of money placed or kept in a bank account, usually to gain interest. (“cash funds which are an alternative to bank or building society deposits”)

- Deposit (verb): Store or entrust with someone for safekeeping. (“a vault in which guests may deposit valuable property”)

Bankers think of deposits as a resource they can lend, hoping to earn enough to pay the interest they have promised and make a profit.

- Lending is a risky business. Borrowers can be late with their payments or default altogether. Debt securities (banks don’t hold stocks) are bundles of loans, and those are risky, too. The same credit risks apply. In addition, if interest rates rise, the prices of the securities fall. Banks forced to sell at a loss (say, because depositors demand repayment now) are less able to repay their depositors.

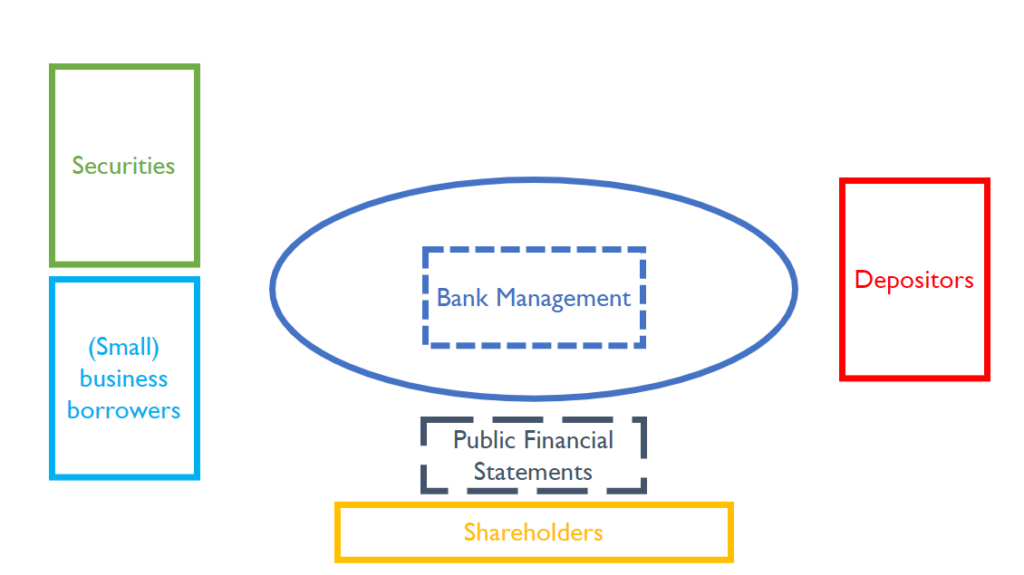

Depositors and shareholders have incomplete and potentially misleading information about their bank’s financial situation.

- The only public information is published in corporate financial reports, which contain information like the summary balance sheet above.

- This information is incomplete and can be misleading. Specifically, the bank can designate some securities as HTM (held to maturity). The bank can then value these securities on the balance sheet at cost rather than recognizing their price changes (“marking to market”) thus ignoring any market value declines due to interest rate increases.

In summary, depositors believe that banks hold their money or invest it very safely, while in fact, banks take significant risk in investing deposits. The publicly available financial information hides this risk from depositors and the public.

In my next article, I’ll dive into banking structure, bank failures, and the regulatory cycle.

This article appeared originally in Forbes.com.

Photo by Jonathan Petersson on Unsplash