This two-article series will examine the role of bonds in your portfolio. We’ll start with a quick review of what bonds are, then move on to factors that influence bond returns. In the next article, we’ll consider some popular ideas for responding to bond risks, then assess rising interest rate implications for both your portfolio and your financial plan.

What are bonds?

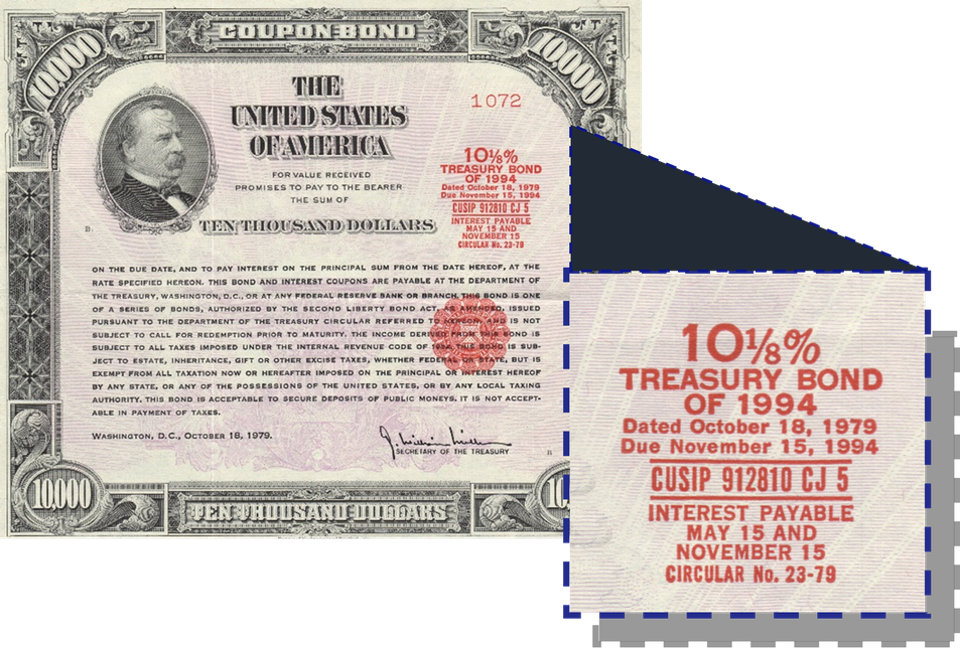

This is a picture of a real US Treasury bond – don’t try to copy and cash it, though – it matured almost 30 years ago! The picture illustrates some basic bond concepts:

- Bonds are loans

- The Face Amount or principal is the amount lent ($10,000 in this case)

- The Issuer is the borrower (the United States of America for this bond)

- The Coupon is the interest rate (101/8% or 10.125%)

- The Issue Date is when loan was made (November 18, 1979)

- The Maturity is when the loan is due (November 15, 1994 – this is a 15-year bond).

Bond returns consist of two components: interest and principal. For the bond shown above, the principal is $10,000. The interest is 1,012.50 per year (10.125% of $10,000). Most Treasury bonds like this one pay interest every 6 months – that would be $506.25 in this case. If the issuer pays interest and principal on time, the bond owner, (the lender) gets exactly what they expect. What could go wrong?

Bond Problems

There are three major categories of bond problems:

- The borrower might not be able to pay. This is called “default.” It could be as simple as the borrower paying an interest payment late, or the borrower being unable to repay the principal. In either case, the borrower is breaking their promise. Lenders become very unhappy, and borrowers are penalized. Corporate borrowers (company management) can get fired, and the lenders can sell off the company’s assets to pay themselves what they are owed. Country and municipal borrowers may not be able to borrow more, or they may face (much) higher interest rates when they try to borrow in the future. No matter the extra costs to borrowers, the lenders are likely to get less than they expected – they lose.

- When interest rates rise, bond prices fall. Zero coupon bonds are the easiest way to see this. These bonds make no explicit interest payments, so lenders are unwilling to lend the full face amount. Instead, they lend a reduced amount, implicitly delaying the “missing” coupon payments until maturity. The table shows the initial price of a ten-year $1,000 zero coupon bond for several different interest rates. For example, lending $905 to receive $1,000 in 10 years yields 1%. If rates are higher, lenders invest less to receive $1,000 after 10 years – if rates are 5%, lenders lend $614 to receive $1,000 in 10 years.

If interest rates start out today at 1% and rise tomorrow to 2%, prices of bonds lenders bought today for $905 will sell for only $820 tomorrow. Prices of bonds issued today will be lower tomorrow because tomorrow’s lenders can negotiate more favorable terms than they could today.

Even though bond prices fall when interest rates rise, borrowers may still be keeping their promises: paying the interest and principal when they’re due. Lenders aren’t losing, they are just disappointed that they could have done better by waiting to lend. Lenders do lose if they intended to sell before maturity (we’ll see more about this later.

3. Unexpected inflation means that coupons and principal payments buy less than they would have had there been no inflation. This is not the fault of borrowers – they

make their promised payments. Unfortunately, lenders have no good solution to this problem. Inflation reduces the purchasing power of all assets denominated in

dollars including especially cash and bonds.

So, why are bonds down?

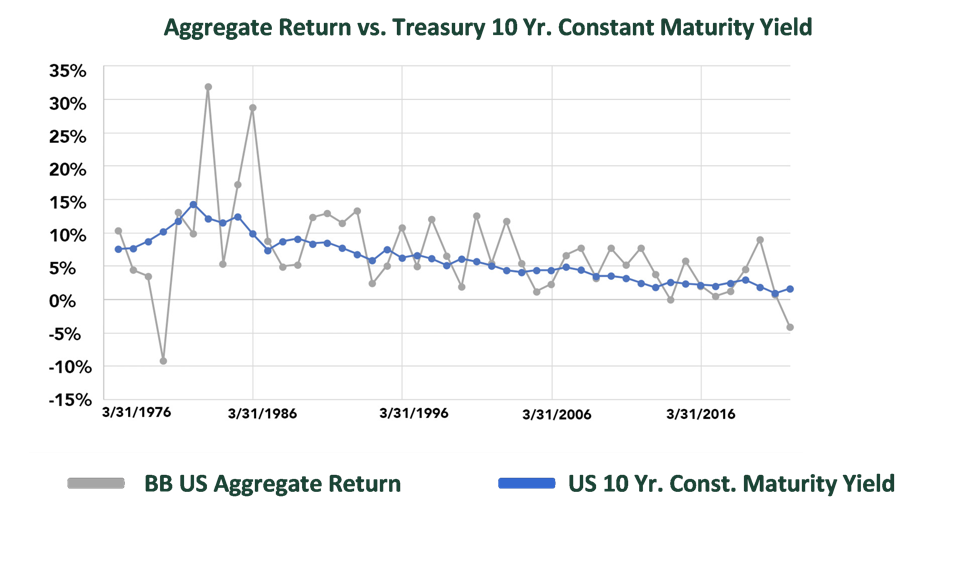

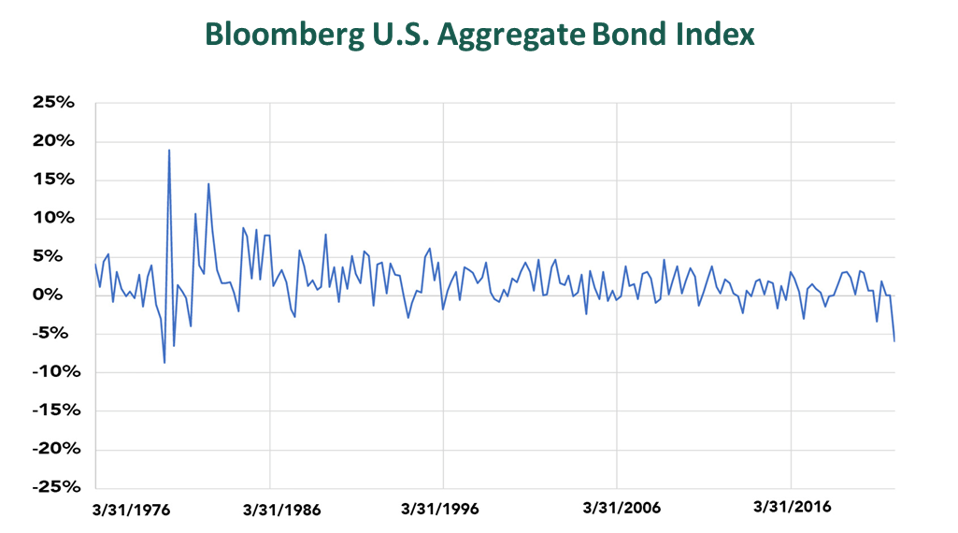

After understanding the basics, we can move on to look at bond performance. We’ll focus on the Bloomberg Fixed Income Indices – a widely accepted indicator of the broad US bond market. The graph shows (in gray) the annual performance (fiscal years ending March 31) of the index since 1976 – it’s been trending down and there has been a good deal of fluctuation. There have been very few years with losses (1980, 2014, 2022).

The graph shows the total return of the index, both interest and capital gains or losses. The blue line shows the yield or interest return on the ten-year US Treasury bond. The index contains ten-year Treasury bonds, but also includes many other kinds of bonds (including mortgage-backed bonds and corporate bonds), and many different maturities. We are asking a lot of our one interest rate or yield. That rate has been trending down also, but its trend obviously doesn’t explain all the variation in annual total return.

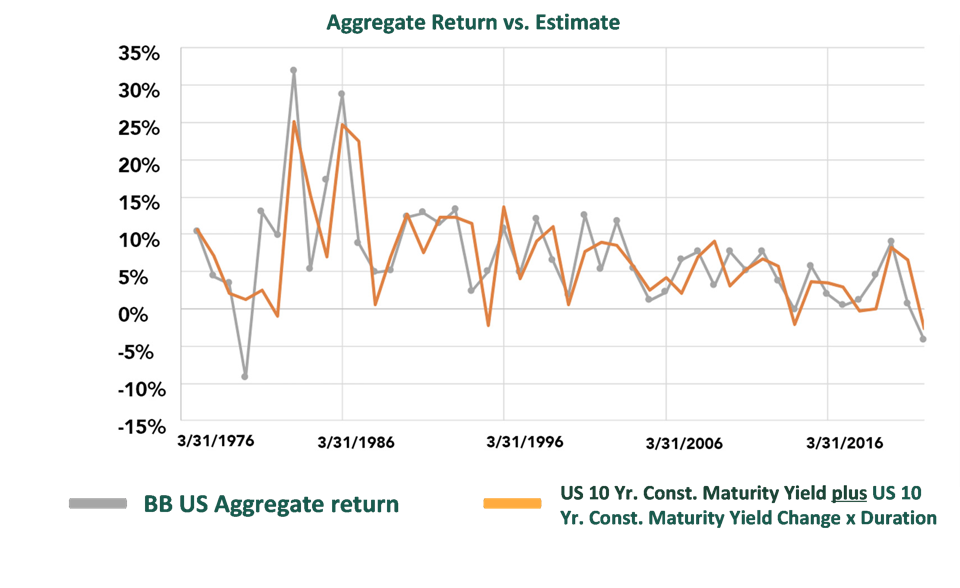

But total return equals interest plus price change. Suppose we add in the price change implied by changes in the 10-year Treasury rate. Notice that the 10-year rate moved up in the last quarter. To get the implied price change, we multiply the interest rate change by the duration of the US Aggregate, approximately 6. (More about this later.) The estimated total return is shown by the orange line. The orange line and the gray line don’t match up perfectly – there is a lot of variation in the US Aggregate return that the 10-year Treasury bond return and changes in it don’t explain. Still, the alignment is pretty good – we have a fair sense of what is going on. Fundamentally, the (approximately .72%) increase in the ten-year Treasury interest rate from fiscal 2021 to fiscal 2022 led to a sharp decline in the US Aggregate return, enough to make the total return negative (-4.2%) in the year ending March 31, 2022.

Importantly, there are no defaults here, no borrower failures to pay. This is simply interest rates rising, and lenders saying they wish they’d gotten the higher interest rates once they appeared.

I thought bonds were safe!

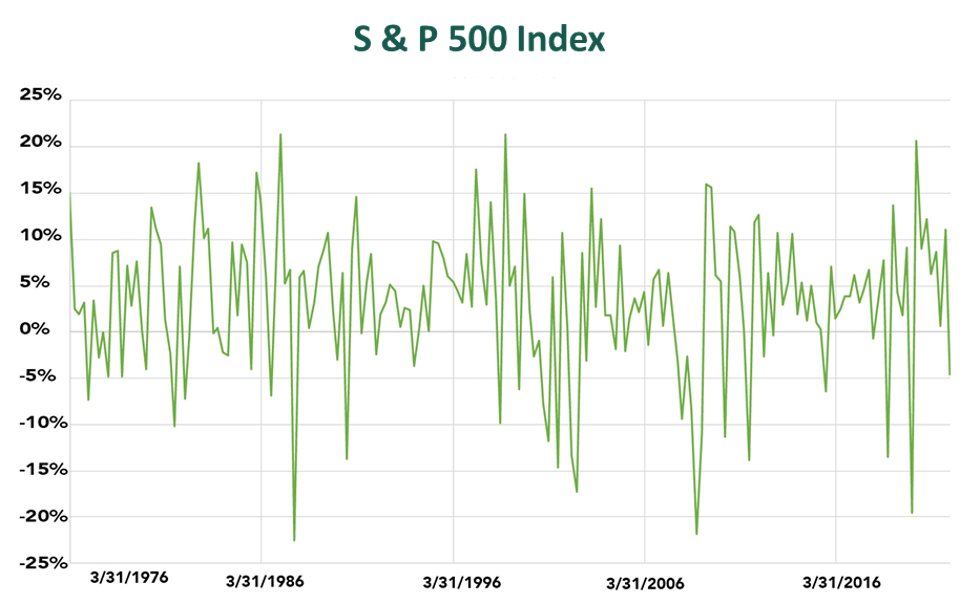

So, bonds are risky – their prices can go down as well as up. But bonds are not nearly as risky as stocks (graphs below are quarterly stock return data since 1976). Stocks have many more negative return quarters than bonds and much larger negative return quarters than bonds.

Can we manage for better bond returns?

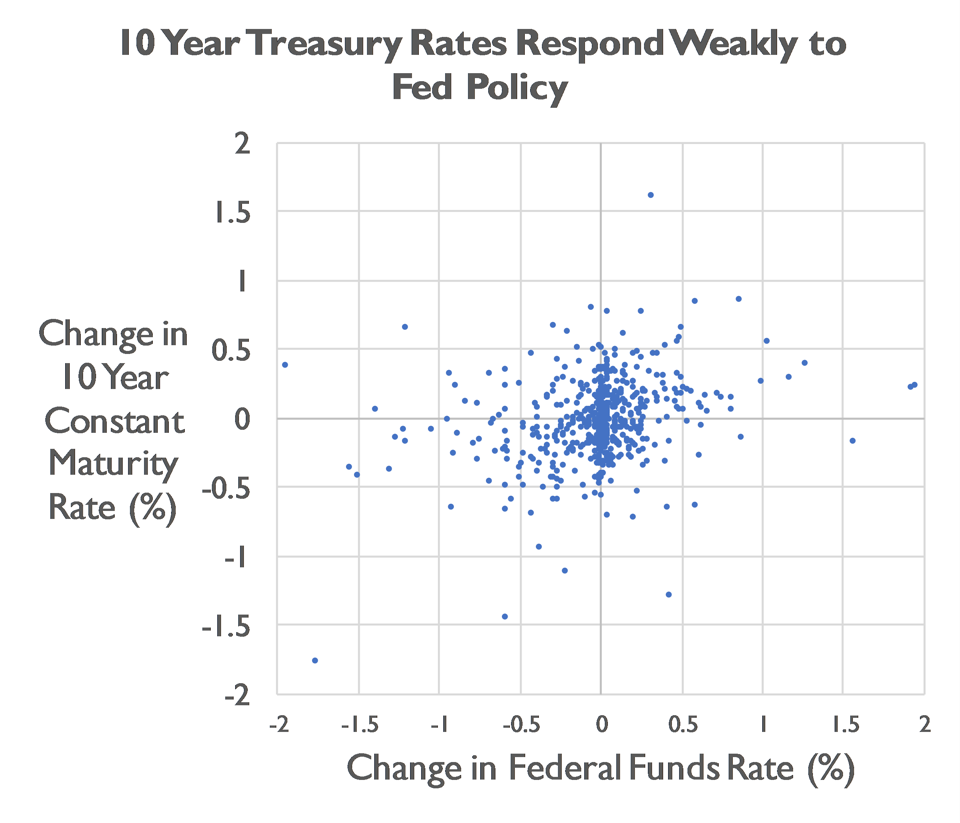

We might ask, though, couldn’t we avoid those negative bond returns? It looks difficult – lots of fluctuation, just like stocks, but … shouldn’t it be easier? After all, the Federal Reserve controls interest rates, right?

Let’s look a bit more closely. Federal Reserve Bank policy controls the Federal Funds interest rate, not all interest rates. We can compare changes in the 10 Year Treasury Constant Maturity Rate to changes in that Federal Funds Rate. We are seeing changes in both rates occurring in the same month, so we can’t determine causation, but we can assess correlation.

There is a hint of upward sloping here, but just a hint. There is a statistical correlation, but it is small. The same is true if we look at changes in the Federal Funds rate for prior months or future months. In short, other factors are important in moving the 10 Year Constant Maturity Treasury Rate, including the supply and demand for credit and general economic activity.

Ideal bond management would be to:

- Sell just before interest rates rise

- Buy exactly when interest rates stop rising

- But, if interest rates are rising slowly, we may get better than cash returns just by holding on

Can we do that? We’ve looked at Federal Reserve actions as predictors of interest rate movements. Even knowing Federal Reserve policy (which all investors do at the same time) isn’t enough to help accurately predict changes in the ten-year Treasury rate – which is a rate that many bond market participants track. In short, just like the market for stocks, the market for bonds is an efficient information processor. It has many participants, all avidly interested in the direction of interest rates. Sadly, while making money by market timing bonds could be extremely lucrative, intense competition makes even moderate success extremely unlikely.

Summary

- All assets are risky

- Bonds are safer than stocks

- Bonds represent promises to pay interest and return principal

- Higher interest rates are more attractive promises – prices of old bonds decline

- Bond returns include interest payments and price changes

- Interest rate (and bond price) changes are unpredictable

In the next article, we’ll consider how to respond to bond risks, then assess the implications of rising interest rates on both your portfolio and your financial plan.

This article originally appeared on Forbes.com.

All written content is provided for information purposes only. Opinions expressed herein are solely those of Sensible Financial and Management, LLC, unless otherwise specifically cited. Material presented is believed to be from reliable sources, but no representations are made by our firm as to other parties’ informational accuracy or completeness. Information provided is not investment advice, a recommendation regarding the purchase or sale of a security or the implementation of a strategy or set of strategies. There is no guarantee that any statements, opinions or forecasts provided herein will prove to be correct. Past performance may not be indicative of future results. Indices are not available for direct investment. Any investor who attempts to mimic the performance of an index would incur fees and expenses which would reduce returns. Securities investing involves risk, including the potential for loss of principal. There is no assurance that any investment plan or strategy will be successful.

Photo by Jaakko Kemppainen on Unsplash