This is Part 2, of a 3-part series, read the other parts here: Part 1, Part 3.

In my previous article, I noted the (surprising) fact that although most financial planners recommend people delay filing for Social Security until age 70, when the benefit will be highest, only about 1% of Americans actually do this. In this article, I’ll answer the common question “How long will I have to have lived in order for delaying Social Security to pay off?” using a breakeven analysis. I’ll then explain why I think this method is flawed.

A breakeven analysis example

Delaying Social Security retirement benefits is a trade-off. In exchange for waiting until some future point (age 70 will maximize your retirement benefit), you will receive higher payments for life. If those higher benefit payments continue for long enough (the Social Security breakeven point), you will have been better off waiting. If you die before the breakeven point, you would have been better off taking your benefit early.

Let’s take a simple example. Dana will retire when she turns 66 on June 1st of this year. She will be entitled to a monthly Social Security retirement benefit of $2,639 (the maximum for 2016) if she files for her retirement benefit when she turns 66. Alternatively, she can delay taking her benefit until 70, which would allow her benefit to grow 32% (or 8% per year) in addition to the annual inflation adjustment. If she waits, her monthly benefit at 70 will be $3,483.

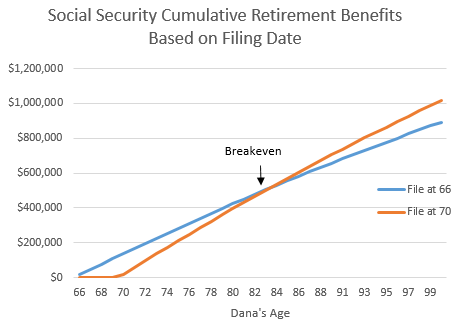

The graph shows Dana’s cumulative lifetime benefits as a function of her filing age. To calculate this benefit, I’ve assumed a real rate of return of 1% (this is about equal to what you could receive today from Treasury bonds).

You’ll notice that Dana’s breakeven point is her age 83. At this point, the cumulative benefit she would receive from waiting until age 70 is greater than the cumulative benefit she would have received had she filed for benefits at age 66. Importantly, every year she lives past 83, the better off she is for having waited. If she lives to 100, she will have been better off by approximately $125,000.

The pitfalls of a breakeven analysis

Many people see the above analysis and conclude that taking an early benefit is in their best interest (remember, only ~1% of Americans delay their benefit until age 70!). Below are some of the more common arguments along with my thoughts.

- I’ll never live that long, so why should I wait until 70? If you have health issues or if your family does not have a history of longevity, it’s true that you might be better off claiming your Social Security benefit sooner than later. However, if you are of average health and you do not need the income immediately, you should strongly consider delaying. (Society of Actuaries Retirement Participation 2000 Table). Once you retire, the real danger is not dying too early, it’s outliving your savings. The best way for most people to insure against that risk is to delay Social Security.

- “A bird in the hand is worth two in the bush”. The idea that taking Social Security “now” rather than “later” is somehow safer is another common argument I hear. Let’s be clear: Social Security is fantastic insurance. It’s an inflation-adjusted annuity that has zero default risk. There is simply no substitute for it in the market. And although the Congressional Budget Office estimates that changes will have to be made by 2033 to prevent a shortfall, that’s a long time from now and there are many options for shoring up the system. I think people who make this argument are not really worried that Social Security won’t be there in another couple years. They are worried about losing money. Statistically speaking, people feel twice as bad about a loss as they feel good about an equivalent gain. It follows that if you focus on the potential loss that would occur by delaying your benefit and dying prematurely, you are more likely to file early. This is another failure of breakeven analysis. Instead of viewing Social Security as an investment, I suggest you think about it as insurance against the worst-case financial scenario, i.e., living a very long time. I’ll bet you didn’t run a breakeven analysis when you bought life or homeowner’s insurance (if you did, you’d never buy it!). Instead, you probably focused on the worst-case scenario, e.g., dying prematurely or your house burning down in a fire, and decided it was in your best interest to transfer that risk to an insurance company. The same thought process applies to Social Security.

- If I take my benefit early, I can do better in the stock market than I could otherwise. In my analysis, I used a real rate of return of 1% to calculate Dana’s cumulative lifetime benefit. If I increased this rate to something higher, let’s say 4%, Dana’s breakeven point changes from her age 83 to 89. That’s because as the discount rate increases, the present value of your Social Security benefit decreases. So while it’s true that if stocks were to yield consistently high real rates of return, you might be better off taking Social Security early and investing the rest. But comparing Social Security benefits to stock returns is a mistake. Social Security is a government-guaranteed, inflation-adjusted annuity. There is no guarantee that stocks will have a positive return. Frequently, their returns are negative. The proper comparison is Treasury bonds, which are government-guaranteed and yield approximately 1% real today. Using this rate, most people would be better off delaying their benefit if they live to their early 80s.

Conclusion

In sum, a breakeven analysis is a flawed way to analyze Social Security. Nevertheless, it’s awfully prevalent. Try typing “social security break even” into a Google search and see how many results it yields. When I did this myself, I got about 11 million results, including articles from major publications such as U.S. News and Forbes.

But if analyzing Social Security based on your lifespan isn’t a sound method, how can you measure the value of delaying Social Security? In my next article I’ll explain how you can compare Social Security to a comparable product, in this case an inflation-adjusted annuity from an insurance company, to better quantify Social Security’s retirement benefit.