When you choose your housing in retirement, you have different objectives and circumstances than you did earlier in your life:

- You might prefer a single-story residence, or want room for your adult children or an aide to move in.

- You may wish to allow for possible changes in your physical abilities as you age.

- Your emotional energy is likely to decrease, making it harder to undertake big changes.

When thinking about housing options in retirement, we recommend planning to be flexible without having to be nimble.

If you’d like more detail, you can watch a webinar I presented on this subject. Watch How Much House Can We Afford?

How to think about housing

Housing isn’t like most of your expenses. It’s a large lump investment, not something you spend money on every week or every month. Comparing that one large long-term purchase to regular shorter-term expenditures is hard. That’s why we use a lifetime balance sheet. It lets you view both short-term and long-term expenses like housing. This lets you figure out the effect of home ownership on the rest of your financial plan.

The Robinsons’ retirement housing plans

Our example couple, the Robinsons, want to move out of their family home when they retire. They earn a comfortable living and don’t have to worry about their children, so their focus is their own housing needs.

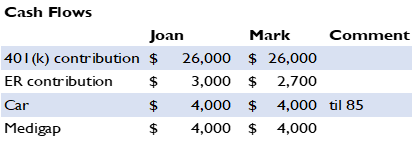

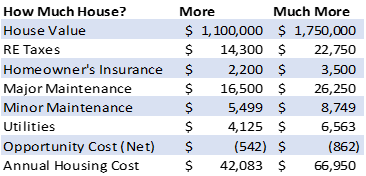

The Robinsons have decided downsizing is not for them. They want to go for the gusto and buy a bigger house in a fashionable area. They also want to maintain their present living standard. They have substantial 401Ks and good-sized checking and savings accounts, which they’re adding to every year.

Lifetime cost difference between two houses

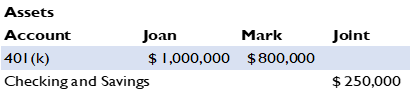

The Robinsons are deciding between two houses. One is nicer than their current house and costs $1.1 million. The other is much nicer and costs $1.75 million. We’re going to focus on how buying each house will affect their lifetime balance sheet.

Here are the differences in the purchase and annual costs of the houses. Annual costs include real estate taxes, homeowners’ insurance, and major maintenance. Purchase cost is an important factor – the money must come from somewhere! The costs don’t end there. Once you buy the house, annual housing costs can be substantial.

Maintenance costs

People often underestimate maintenance costs. Unfortunately, houses don’t last forever – stuff wears out! If you want your house to stay comfortable and maintain its resale value, you have to keep up with major maintenance.

Maintenance expenses occur in large lumps at irregular intervals. The roof doesn’t need to be replaced every year, but when it does, it costs a lot. We estimate major maintenance costs to average two percent of your dwelling’s replacement cost every year.

Opportunity Cost

It’s also important to consider the opportunity cost of the investment – the cost of sinking money into your house instead of your investments, giving up the chance for any potential financial returns. Right now, real interest rates are negative, so the opportunity cost is negative. But if real interest rates were higher, then the opportunity cost would be positive, and that would increase the annual housing cost.

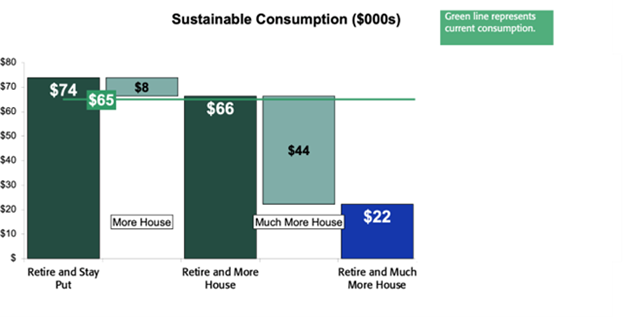

Annual housing costs and retirement spending

- Their lifetime assets are on the left. On the right we see their lifetime spending, including their housing expenditures. Housing expenses are higher than if the Robinsons hadn’t moved.

- Their lifetime sustainable consumption is lower.

- Their lifetime surplus – their financial margin for error, basically – has become very small, just $39,765.

All that money is going into the house. There’s no wiggle room.

The house the Robinsons are in now is worth $950,000. It’s not even that different from the $1.1 million house. The Robinsons aren’t too happy. They wonder whether there’s anything they could do to enjoy a nicer, larger house for a while. Well, there is.

Upgrade, then downgrade

Here’s the Robinsons’ new plan. They’re going to buy that $1.75 million house after all. They’ll live there for 10 years. By then they’ll be in their 80s. They probably won’t feel up to throwing big parties or climbing lots of stairs anymore, so they won’t mind downsizing to a smaller place that costs $750,000.

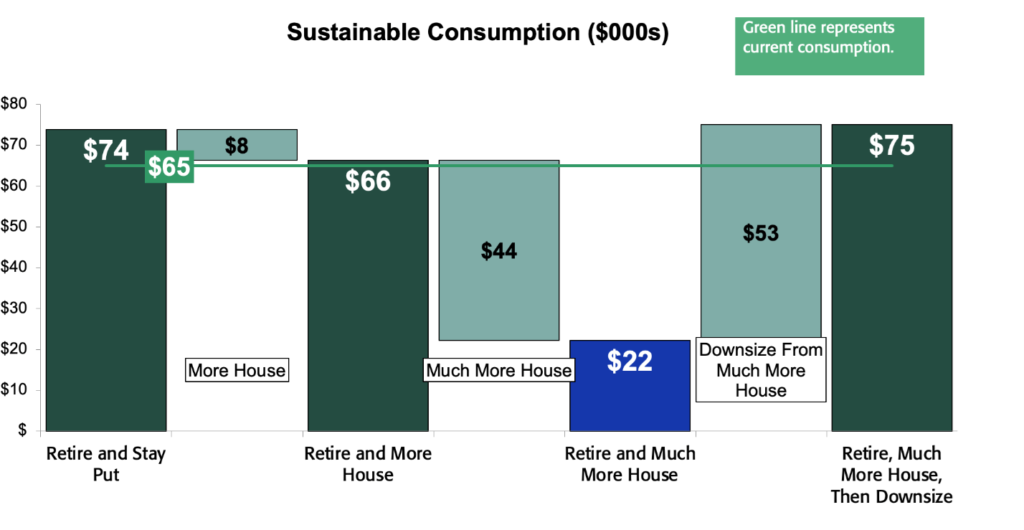

This looks like the perfect solution! If the Robinsons retire, buy the big house, then downsize, here’s what they get:

- They can spend $75,000 a year. That’s about the same they would have spent if they stayed in their current house.

- They’ll have just as much surplus as they would have had before.

- They get to spend 10 years in a big house near the city. Then they can move somewhere cozy with one story in their 80s.

What’s not to like?

There are a few potential issues.

- The older you get, the harder it is to move. This plan requires them to move at age 80.

- They’re under a lot of financial pressure to move at 80. Because of the high costs of the house on top of their annual spending, the Richardsons could run out of retirement savings at 86 if they don’t downsize at 80.

- If the value of the $1.75 million house falls a lot, their plan is ruined. If the housing market doesn’t cooperate, the Richardsons might not be able to get the funds they need when they sell the house.

This plan looks perfect financially. But being perfect for your finances isn’t enough – your plans have to work on a practical level. If the Richardsons commit to this plan, they must downsize at 80, even if they don’t feel like it when they get there.

So, how much house can you afford when you retire?

It really depends on you.

Buying a more expensive house implies higher annual costs. But if you plan to hold onto that house for the rest of your life, that means you’re leaving a larger bequest. You can plan to downsize later, but moving gets harder as you age, and there are investment risks because you might not be able to get as much equity out of the house as you expected. That’s significant because preserving financial flexibility becomes more important when you retire, because you’re no longer earning income from work.

Feel free to go to the open house for that mansion near the city, but don’t forget to keep annual costs and financial flexibility in mind before you make any big decisions. And if you’re still not sure whether you can afford to upgrade to a more expensive house in retirement, give us a call.

This article summarizes a recent interview with a current client of Sensible Financial. Sensible Financial did not compensate the client in any way and is unaware of any conflict of interest.

Photo by Stephan Bechert on Unsplash