Prepaying your mortgage can be a sensible thing to do, especially when you have idle savings (think cash or money market accounts not earmarked for specific financial goals or your emergency fund) earning less than the rate on your mortgage. In my previous article, I analyzed the mechanics of prepaying your mortgage. In effect, prepaying your mortgage triggers a cascade effect that ultimately speeds up the repayment of the loan. In what follows, I’ll discuss when prepaying your loan makes good financial sense.

Pay down debt when borrowing costs are high

Fundamentally, the question of whether to prepay your mortgage (or any debt, for that matter) depends on whether you can save more in borrowing costs than you would make in lending interest. When you have a mortgage, you are a borrower. When you borrow money from the bank, you pay interest on the amount you borrow. Alternatively, when you own an investment, you are a lender. When you lend money to (make deposits in) the bank, for example, you receive interest on the amount you lend. Ultimately, if you pay more in interest to borrow money than you receive in interest to lend money, then you are better-off using idle savings to pay down your debt than you are by investing it elsewhere (and vice versa). Simply put, you should accelerate debt payments when the following is true:

Borrowing Cost > Lending Benefit

Amortized loans (like your mortgage) calculate interest payments based on the outstanding balance of the loan. Putting taxes aside for the moment, this makes analysis rather straightforward. No matter how large an extra payment you make, or when you make it, the cost of borrowing (excluding property tax and insurance payments) will always be exactly equal to the interest rate you pay on your mortgage.

Now, consider the benefits of lending money. Rather than putting additional money towards your mortgage, you could invest the money elsewhere. For example, you can buy stocks, bonds, or lend your money to the bank. (Hey, you could even lend money to your unreliable cousin!) In each case, you can expect to receive ongoing payments from the borrower based on the amount you lend. For bonds or certificates of deposit (CDs), this is the interest you receive from the borrower. For stocks, this is the share of company earnings (or dividend) you receive from the borrower(s).[1] Importantly, each type of investment carries a different level of risk.

Prepaying your mortgage is like investing in a risk-free bond

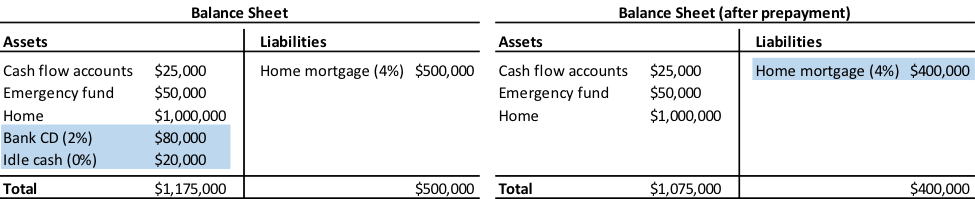

Consider the balance sheets below. Before prepayment (left), on the asset side, there is $25k in working cash (for day-to-day expenses), $50k in an emergency fund, a $1m home, $80k in a bank CD earning 2%, and $20k in excess cash. On the liability side, there is a $500k home loan at a fixed rate of 4%. If the bank CD and idle cash were used to prepay the mortgage, each side of the balance sheet would decline by $100k (right). The bank CD and idle cash would no longer be financial assets, and the outstanding balance on the mortgage would decline by the same amount.

In practice, this is entirely accurate. However, from an investment perspective, it is not particularly helpful. Recall that prepaying the mortgage reduces all future interest payments, meaning that more of each monthly payment goes towards your outstanding loan balance. This is equivalent to investing in a risk-free bond. Although you are not technically receiving interest payments from the bank (as you would with a bond), your interest savings are going towards the loan balance, which increases your home equity. Therefore, an alternative way of illustrating the effect of a prepayment on the balance sheet is to leave the mortgage liability at $500k and adjust the financial assets accordingly.

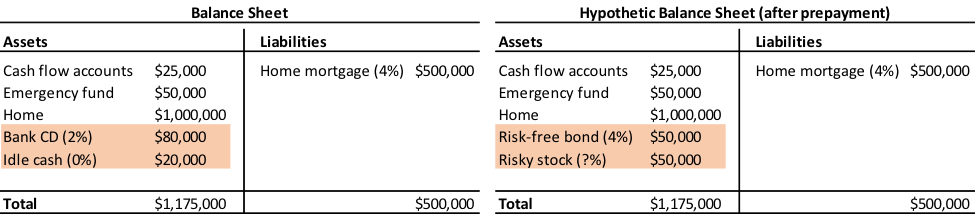

In the next balance sheet pair, money from the bank CD and idle cash is split equally between prepaying the mortgage ($50k) and investing in stocks ($50k). This is functionally equivalent to substituting the $80k bank CD and $20k of idle cash with a $50k risk-free bond earning 4% and $50k in a risky stock portfolio. Total assets and total liabilities remain the same, but the mix of financial assets changes. This allows for a more instructive comparison of prepaying the mortgage with alternative investments.

Comparing extra payments on your mortgage to investing money in the stock market is like comparing apples and oranges.[2] Stock market returns (both dividends and capital gains) are volatile and offer no guarantees. For all intents and purposes, prepaying the mortgage is like investing in a risk-free bond that (depending on rates) may pay more than what you could get on an equivalent risk-free investment. Think U.S. Treasury Bonds or FDIC insured bank deposits or CDs.[3]

The balance sheet perspective highlights another important point. While we think of our home mortgage as financing our home (and our home is collateral on the mortgage), it also finances our other investments. Prepaying the mortgage is equivalent to financing a risk-free bond. Investing your cash in stock instead of prepaying your mortgage is equivalent to using your mortgage to finance stock investment.

For the most part, you can ignore taxes

When you lend money to the U.S. government or a bank, or purchase company stock, the interest income is taxable.[4] Therefore, as a lender, you should compare after-tax rates of return. In parallel, thanks to the home mortgage interest deduction (HMID), when you borrow money from the bank to buy, build, or improve your first or second home, the interest payments on your mortgage(s) are tax deductible (up to a total of $1 million of debt) for those who itemize their deductions. This means that as a borrower, you should focus on your after-tax interest rate.

Think back to the decision rule above. If we include taxes, the rule can be restated as follows. When the (after-tax) cost of borrowing is greater than the (after-tax) benefit of lending, you are better-off paying down debt.

If you can take full advantage of the HMID then the cost of borrowing is simply the stated rate reduced by your marginal income tax rate. For example, if the interest rate on your mortgage is 4% and your ordinary income tax rate is 25%, then your after-tax cost of borrowing is 3% (4% x (1 – 25%) = 3%). In effect, the HMID reduces the effective rate you pay on your loan.

However, if you cannot take full advantage of the HMID then the cost of borrowing is reduced by less than your marginal income tax rate. This can occur if your adjusted gross income (AGI) is sufficiently high to limit your itemized deductions or if you rely on your mortgage interest to make itemizing your deductions worthwhile.[5] In the example above, this means your after-tax cost of borrowing is higher, falling between 3% and 4%. A smaller tax savings means a higher after-tax cost of borrowing. All else equal, this makes paying down debt even more attractive.

The same rule applies to the after-tax benefit of lending. For example, if the interest rate on 30 year U.S. Treasury Bonds is 4% and your ordinary income tax rate is 25%, then your after-tax benefit of lending (i.e., after-tax rate of return) is 3% (4% x (1 – 25%) = 3%). Income taxes reduce the effective interest rate you receive on your lending

Fortunately, whether you get the full benefit of the HMID or not, you can boil everything down to the following simple rule. You are better-off using idle savings or cash to prepay your mortgage if the rate on your loan is greater than the rate on U.S. Treasury Bonds or bank savings accounts or CDs. If you cannot take full advantage of the HMID, then this makes prepaying the mortgage an even better investment.

Conclusion

Whenever you consider putting extra money towards your mortgage, you can think of it like investing your money at a guaranteed rate at least as large as your loan interest rate. For the most part, because the mortgage interest you pay is tax deductible and any interest you receive is taxable, you can ignore taxes. This means that you can easily compare the rate on your mortgage to the rate on an equivalent risk-free investment. Investing in the stock market, on the other hand, offers no guarantees. If you have a great deal of idle savings or cash, and the rate on your loan is greater than (or equal to) the current rate on taxable U.S. Treasury Bonds (for example), then you should think seriously about prepaying your loan. If you have any questions about your personal situation or whether this makes sense for you, please leave a comment or contact your advisor.

[1] Some companies do not pay dividends, instead reinvesting all their earnings back into the company in hopes of future growth.

[2] Stocks, unlike U.S. Treasury Bonds, have a large risk premium because of their volatility. Therefore, to accurately compare prepaying your mortgage to investing in the stock market, stock returns would need to be discounted at a much higher rate than the rate on your mortgage.

[3] U.S. Treasury Bonds are backed by the full faith and credit of the U.S. government and bank deposits and CDs (up to certain limits) are backed by the Federal Deposit Insurance Corporation (FDIC). Default risk is essentially nil.

[4] Interest income from U.S. Treasury Bonds and bank savings accounts or CDs are taxed as ordinary income. Qualified stock dividends, on the other hand, are taxed at capital gains rates.

[5] All tax filers get a standard deduction on their taxable income ($6,350 for single filers and $12,700 for married couples filing jointly in 2017). Therefore, to get the full benefit of the HMID one would need to have other itemized deductions equal to at least the standard deduction. The HMID is also limited for those with large AGIs ($259,400 for single filers and $311,300 for married couples filing jointly in 2017). https://www.irs.gov/publications/p17/ch29.html#en_US_2016_publink1000300882

To speak with an advisor about planning for your financial future, contact us!