Most of the financial planning industry focuses on advising people at or near retirement with a large amount of financial assets. Modern financial planning evolved from a stockbroker model and still focuses on investment management and most people don’t focus on planning for retirement (their largest financial goal) until middle age.

Ironically, young people may benefit more than their elders from sound financial advice. A 30-year-old can implement changes that can make a material difference to her long-term financial plan. By comparison, when a client comes to us at age 65 to do a financial plan there is not as much they can do to change the picture.

In this article, I will focus on two financial issues we’ve identified as important to people at different points in their lives: human capital management, and living within your means. For each issue I’ll provide a brief description and offer some sensible advice that young adults can incorporate into their own financial plans. (You can find a more complete treatment of our financial planning approach here in our Financial Planning Guidebook, which is free to download).

Human Capital Management

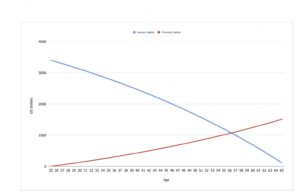

Human capital is the sum of your lifetime earning potential. When you’re young, human capital is often your largest asset. As you near retirement it shrinks as fewer earning years remain. Throughout our working lives we convert human capital into financial capital (savings) to fund spending in retirement.

Imagine a 25-year-old who earns $120,000 per year and retires at 66. When she starts her career, she has $3.5 million in human capital – the sum of her future earnings discounted to today. Over time, she saves what she doesn’t spend, converting human capital into financial capital. When she retires, her savings of approximately $1.5 million is enough to fund retirement (there’s nothing special about this number and everyone’s “nest egg” differs – this is simply an example).

Human capital management is the process of handling your earning potential over time. There are several financial planning implications for young adults to consider:

-

Invest in your career – Your lifetime earnings will impact your financial plan more than any other factor. Think long and hard about what kind of career you want for yourself. Pursuing a more remunerative career will produce more financial resources but will likely come at the cost of less time to do other things you love. The industry you choose can have a huge impact on your career path – for example, teachers and nurses can work more easily through their 60s than professional athletes. Diversify your skillset to protect yourself against the inevitable technology advances that can massively disrupt or even destroy professions overnight.

-

Build your network – It’s unlikely you will have only one job (or perhaps even one profession) over your career. Develop connections with people in your industry and cultivate those relationships over time. If you lose or quit your job it will be much harder to transition to a new one if people don’t know who you are.

- Think hard about what money means to you – When we start out as young adults, living on our own for the first time and making money, it can be tempting to live a cash flow-based life and spend what comes in. But we’re all constrained by a finite amount of human capital to spend over our lives. Understanding early on how you want to allocate this resource is extremely important. It will inform decisions such as when you can retire, where you choose to live, perhaps even what kind of family you choose to have. Books like Happy Money can provide valuable insights into our personal values and how money does (and does not) lead to happiness.

- Protect your human capital with life and disability insurance – No one likes to think about death or disability, but the financial impact of these (unlikely) events is greatest when we’re young. Recall our 25-year-old professional with $3.5 million in expected lifetime earnings. If she dies prematurely and she’s married, life insurance will protect her partner and possibly children. If she becomes disabled for an extended time, disability insurance could replace enough of her earnings to protect her from financial ruin.

- Life insurance – Life insurance exists primarily to protect those who depend on your earnings if you die prematurely. If you are married, you should get a policy to protect your loved ones. If you are not married, you still may wish to get a policy for two reasons. One, if you marry or partner in the future, getting a policy today eliminates the risk that a future health event could increase the cost of insurance to you. Two, even if you never marry, a life insurance policy could provide protection in case of a terminal illness with a viatical, or life, settlement. Consider buying a 30-year term policy sooner than later. You may be able to add insurance in the future if your situation changes.

- Disability insurance – If your company offers group disability insurance, buy as much as you can. The general rule is if you pay the premiums then any benefit will be tax-free to you. If your employer pays, the benefit is taxable. Given the choice, always pay the premium yourself. Group disability insurance is usually capped at some percent of earnings or a monthly dollar maximum. Consider a private policy to increase coverage. As a general rule, you should try to cover at least two thirds of your income (insurers are unlikely to provide coverage above this amount). Private disability insurance is not cheap, but you’ll be glad you have it in an emergency. To reduce the cost, include taking a larger elimination period and looking into policies provided through a professional group or trade association.

Living within your means is a form of financial planning

Financial planning is an asset-liability matching problem. People have a certain amount of (lifetime) assets they can use to fund (lifetime) liabilities. Living within your means simply recognizes that you can’t spend more during your lifetime than you have in lifetime resources.

We can extend the above human capital model to include lifetime expenses. Doing so allows us to construct a person’s lifetime balance sheet. This lifetime balance sheet allows us to solve for a person’s lifetime discretionary budget, which is simply the difference between lifetime assets and lifetime fixed expenses.

When you’re young it can be difficult to figure out your lifetime budget. With many possible income and spending scenarios, calculating your lifetime budget can feel overwhelming. Nevertheless, even without perfect knowledge of the future there are things you can do today that will put you in a better position in the future when you are ready to do a full a financial plan.

- Understand where your money goes – At least once a year you should review your spending. Knowing how much you can afford to spend over your lifetime isn’t required. Sometimes just seeing how you spent your hard-earned dollars can lead to improvements. Some people are surprised when they see how their morning coffee multiplied by 261 workdays adds up to a small vacation. For others, it’s the insight that having paid $2,000 on streaming services which they rarely use might be repurposed. Whatever the case, most people find it valuable to review their spending periodically.

- Some popular programs to track spending include Mint, Quicken and You Need a Budget. Some services are “free” but use your data. If you are concerned about privacy consider a paid service.

- If the idea of reviewing multiple $2.50 transactions and categorizing them gives you a headache, many credit cards now produce annual statements that break down spending into categories for you automatically. Some companies produce these reports automatically while others require users to request such reports. Be aware that before the computers become smart enough to take over all our jobs, they still make mistakes categorizing spending. But with an hour or so of your time you should be able to put together a reasonably accurate annual spending report.

- Consider making a budget – especially if you are overspending – Let’s make a distinction between tracking spending and budgeting. The former tells you what you’ve spent already. The latter is a plan for what to spend in the future. Not everyone needs to budget prospectively. However, two things argue in favor of doing it: one, if after tracking spending you want to make major changes moving forward; and two, if you consistently spend more than you earn. Making a budget can help you gain control of your spending and it’s a useful skill that may help you in the future.

- If you prefer a software solution consider something like You Need a Budget. You can create budgets and track them over time using a computer or smartphone. You can also create a simple paper budget. Ultimately there’s no one right solution, just the solution that works best for you.

Managing your human capital and living within your means are fundamental to your financial plan. Hopefully the above suggestions provide a useful starting point to tackle these important issues.

Photo by Christina @ wocintechchat.com on Unsplash